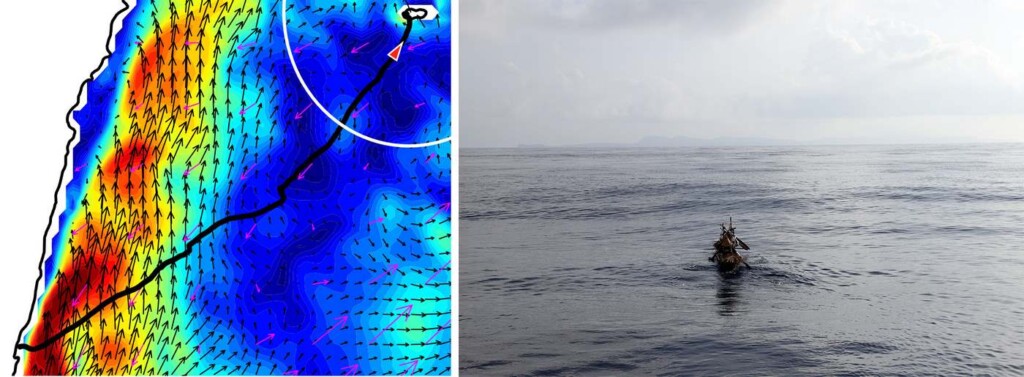

The team in action on their 30,000 year old canoe – credit University of Tokyo A team of scientists who could only be described as ‘intrepid’ sailed several hundred miles across the East China Sea in an ancient replica canoe. The peopling of the Pacific islands has long been one of the great mysteries of anthropology, and the Japanese researchers wanted to do their own small part in unraveling it by answering a question: how did Paleolithic people get from Taiwan to Japan’s southernmost island of Yonaguni.  A map of the team’s canoe voyage from Taiwan to the Japanese island of Yonaguni credit – University of Tokyo While the distance of 140 miles isn’t mighty when compared to some of the voyages the Polynesians are known to have made, it crosses an area plied by one of the strongest currents in the world called the Kuroshio. In two new papers, researchers from Japan and Taiwan led by Professor Yousuke Kaifu from the University of Tokyo simulated methods ancient peoples would have needed to accomplish this journey, and they used period-accurate tools to create the canoes to make the journey themselves. Of the two newly published papers, one used numerical simulations. The simulation showed that a boat made using tools of the time, and the right know-how, could have navigated the Kuroshio. The other paper detailed the construction and testing of a real boat which the team successfully used to paddle between islands. “We initiated this project with simple questions: How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? How difficult was their journey? And what tools and strategies did they use?” said Kaifu in a press release from the University of Tokyo. “Archaeological evidence such as remains and artifacts can’t paint a full picture as the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away. So, we turned to the idea of experimental archaeology, in a similar vein to the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947 by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl.” The Kon-Tiki expedition was a fantastic exercise in getting out of the library, as Indiana Jones said. Seeking to confirm his theory that prehistoric humans may have sailed across the Pacific, Heyerdahl recruited an international team of sailors, craftsmen, explorers, and scientists, and built a raft of primitive materials called Kon-Tiki, which they used to sail from South America to the Tuamotus, across more than 3,000 miles of open ocean. In 2019, the Taiwanese-Japanese team constructed a 23-foot-long dugout canoe called Sugime, built from a single Japanese cedar trunk, using replicas of 30,000-year-old stone tools. They paddled it 140 miles from eastern Taiwan to Yonaguni Island in the Ryukyu group, which includes Okinawa, navigating only by the sun, stars, swells and their instincts. They paddled for over 45 hours across the open sea, mostly without any visibility of the island they were targeting. Several years later, the team is still unpicking some of the data they created during the experiment, and using what they find to inform or test models about various aspects of sea crossings in that region so long ago.  A single Japanese ceder tree was used to make the canoe – credit University of Tokyo Kaifu monologued about the team’s findings and revelations, a full 6 years after their expedition. “A dugout canoe was our last candidate among the possible Paleolithic seagoing crafts for the region. We first hypothesized that Paleolithic people used rafts, but after a series of experiments, we learned that these rafts are too slow to cross the Kuroshio and are not durable enough.” “We now know that these canoes are fast and durable enough to make the crossing, but that’s only half the story. Those male and female pioneers must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown.” “Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance. For example, the ancient Polynesian people had no maps, but they could travel almost the entire Pacific. There are a variety of signs on the ocean to know the right direction, such as visible land masses, heavenly bodies, swells, and winds. We learned parts of such techniques ourselves along the way.”  GPS tracking and modeling of ocean currents toward the end of the experimental voyage – credit, Kaifu et al. CC ND-BY One interesting note was that the team felt any return journey would have been much more difficult, if not altogether impossible, in part because the Kurushio current is varied, and facing it in reverse would have been even tougher. According to the teams’ data, on a vessel launched off the eastern coast of Taiwan as theirs’ was, the Kuroshio runs hard northward along the coastline. Throughout their paddling, they had to compensate for a headwind, and the current seeking to pull them back north. Their GPS trail shows that they missed several zones of deep water where the Kuroshio changes and begins to tug eastward, as well as an area where the current forms something like an ocean gyrate that could have sent them in multiple directions. They navigated the hazardous current brilliantly, but to do so in reverse would have been extremely difficult. They would have been moving against the current in all periods, and from the start it would be trying to pull them out to open ocean.“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were. One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers.” Scientists Use Stones to Build Canoe Like Their Ancestors and Sailed it 140 Miles Across Dangerous Waters |