Charles Kemp, The University of Melbourne; Ekaterina Vylomova, The University of Melbourne; Temuulen Khishigsuren, The University of Melbourne, and Terry Regier, University of California, BerkeleyLanguages are windows into the worlds of the people who speak them – reflecting what they value and experience daily. So perhaps it’s no surprise different languages highlight different areas of vocabulary. Scholars have noted that Mongolian has many horse-related words, that Maori has many words for ferns, and Japanese has many words related to taste. Some links are unsurprising, such as German having many words related to beer, or Fijian having many words for fish. The linguist Paul Zinsli wrote an entire book on Swiss-German words related to mountains. In our recently-published study we took a broad approach towards understanding the links between different languages and concepts. Using computational methods, we identified areas of vocabulary that are characteristic of specific languages, to provide insight into linguistic and cultural variation. Our work adds to a growing understanding of language, culture, and the way they both relate. We tested 163 links between languages and concepts, drawn from the literature. We compiled a digital dataset of 1574 bilingual dictionaries that translate between English and 616 different languages. Since many of these dictionaries were still under copyright, we only had access to counts of how often a particular word appeared in each dictionary. One example of a concept we looked at was “horse”, for which the top-scoring languages included French, German, Kazakh and Mongolian. This means dictionaries in these languages had a relatively high number of

However, it is also possible the counts were influenced by “horse” appearing in example sentences for unrelated terms. Not a hoax after all?Our findings support most links previously highlighted by researchers, including that Hindi has many words related to love and Japanese has many words related to obligation and duty. We were especially interested in testing the idea that Inuit languages have many words for snow. This notorious claim has long been distorted and exaggerated. It has even been dismissed as the “great Eskimo vocabulary hoax”, with some experts saying it simply isn’t true. But our results suggest the Inuit snow vocabulary is indeed exceptional. Out of 616 languages, the language with the top score for “snow” was Eastern Canadian Inuktitut. The other two Inuit languages in our data set (Western Canadian Inuktitut and North Alaskan Inupiatun) also achieved high scores for “snow”. The Eastern Canadian Inuktitut dictionary in our dataset includes terms such as kikalukpok, which means “noisy walking on hard snow”, and apingaut, which means “first snow fall”. The top 20 languages for “snow” included several other languages of Alaska, such as Ahtena, Dena'ina and Central Alaskan Yupik, as well as Japanese and Scots. Scots includes terms such as doon-lay, meaning “a heavy fall of snow”, feughter meaning “a sudden, slight fall of snow”, and fuddum, meaning “snow drifting at intervals”. You can explore our findings using the tool we developed, which allows you to identify the top languages for any given concept, and the top concepts for a particular language. Language and environmentAlthough the languages with top scores for “snow” are all spoken in snowy regions, the top-ranked languages for “rain” were not always from the rainiest parts of the world. For instance, South Africa has a medium level of rainfall, but languages from this region, such as Nyanja, East Taa and Shona, have many rain-related words. This is probably because, unlike snow, rain is important for human survival – which means people still talk about it in its absence. For speakers of East Taa, rain is both relatively rare and desirable. This is reflected in terms such as lábe ||núu-bâ, an “honorific form of address to thunder to bring rain” and |qába, which refers to the “ritual sprinkling of water or urine to bring rain”. Our tool can also be used to explore various concepts related to perception (“smell”), emotion (“love”) and cultural beliefs (“ghost”). The top-scoring languages for “smell” include a cluster of Oceanic languages such as Marshallese, which has terms such as jatbo meaning “smell of damp clothing”, meļļā meaning “smell of blood”, and aelel meaning “smell of fish, lingering on hands, body, or utensils”. Prior to our research, the smell terms of the Pacific Islands had received little attention. Some caveatsAlthough our analysis reveals many interesting links between languages and concepts, the results aren’t always reliable – and should be checked against original dictionaries where possible. For example, the top concepts for Plautdietsch (Mennonite Low German) include von (“of”), den (“the”) and und (“and”) – all of which are unrevealing. We excluded similar words from other languages using Wiktionary, but our method did not filter out these common words for Plautdietsch. Also, the word counts reflect both dictionary definitions and other elements, such as example sentences. While our analysis excluded words that are especially likely to appear in example sentences (such as “woman” and “father”), such words could have still influenced our results to some extent. Most importantly, our results run the risk of perpetuating potentially harmful stereotypes if taken at face value. So we urge caution and respect while using the tool. The concepts it lists for any given language provide, at best, a crude reflection of the cultures associated with that language. Charles Kemp, Professor, School of Psychological Sciences, The University of Melbourne; Ekaterina Vylomova, Lecturer, Computing and Information Systems, The University of Melbourne; Temuulen Khishigsuren, PhD Candidate, The University of Melbourne, and Terry Regier, Professor, Language and Cognition Lab, University of California, Berkeley This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Do Inuit languages really have many words for snow? The most interesting finds from our study of 616 languages (2026-02-26T11:37:00+05:30)

Yami Gautam: Watching or working in a film with preconceived notions is not right (2026-01-01T13:32:00+05:30)

IANS Photo Mumbai, (IANS) A cinema hall is the place where the mind should be completely free of any baggage or ideology, that’s what actress Yami Gautam Dhar believes in. The actress, who is currently awaiting the release of her upcoming film ‘Article 370’, has shared that for actors and the audience it’s imperative to look at films with a clean slate and not be affected by any preconceived notion. The past few months have seen polarising reactions from the audiences to films like ‘Animal’ and ‘Dunki’, and the trend seems to continue with ‘Article 370’ given the narrative of the film touches upon a subject that left the country divided in terms of opinions. The actress spoke with IANS ahead of the release of her film and shared about the trend, her journey in cinema and the role of social media in the modern discourse. Talking about the trend of polarising reactions from the audience, Yami, who admits that she hasn’t yet seen the Ranbir Kapoor-starrer ‘Animal’, told IANS: “If you’re working in a film or watching a film with a preconceived notion, you will never be able to enjoy the film or your working process. You won’t be able to have a fair opinion on it if your judgement is already clouded.” The actress further mentioned, “You like it or you don’t like it, that’s absolutely your personal choice and your prerogative, and you must stand by it. But watching a film with an already set mindset is not the correct way to do it.” Manoeuvring the conversation, the actress then spoke about how polarisation has become a part of the society. Yami told IANS, “As far as polarisation is concerned, today there are polarising opinions on everything, it’s not just the films. Social media has only added fuel to the fire because that’s the easiest way to reach out to a huge number of people.” “Having said that, my job as an actor is to chase excellence, bring compelling stories to the forefront, to do good roles and to be a part of good cinema, that is the intention I work with,” she added. The actress also spoke about her upcoming film and shared that the film delves into the modus operandi behind the abrogation of contentious Article 370 of the Constitution of India. Yami said: “ ‘Article 370’ is not just about an army operation, the film tells how the historical event of abrogation of Article 370 was carried out.” The actress has completed almost a decade and a half in cinema having started her journey in films with the Kannada film ‘Ullasa Utsaha’. However, the actress doesn’t set her eyes on the rear view mirror and always looks forward to what’s next. “I really don’t look back at my cinematic journey and I don’t really think like I have been working for so long. I joined the industry at a young age but today, where I stand, I would say that I’m very happy and I own up to my successful films as much as those films that might not have garnered equal amounts of love from the audience, both are very close to my heart,” she said.Produced by Jyoti Deshpande, Aditya Dhar and Lokesh Dhar, ‘Article 370’ is slated to release in cinemas worldwide on February 23. Yami Gautam: Watching or working in a film with preconceived notions is not right | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

A Historical Step in the Naga Journey Towards a Future of Wholeness (2025-07-31T12:41:00+05:30)

Seen in this photograph are some of the Naga Delegation members in the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. The delegation comprising of leaders from several Naga Tribe Hohos, members of the Forum for Naga Reconciliation and the Recover Restore and Decolonise team were hosted by PRM from June 8-June 14 to explore a pathway for the return and future care of Naga ancestral human remains. The PRM holds the largest Naga collection in the world. Altogether, around 219 Naga ancestral human remains are under their care, of which 41 are skeletal human remains. (Photo Credit: PRM) Lecture Hall of the Museum of Natural History, Oxford University June 13, 2025 aküm longchari In October 2015, the student-led protest movement Rhodes Must Fall tweeted that “The Pitt Rivers Museum is one of the most violent spaces in Oxford.’ Today, walking around the PRM and Oxford, amid history, we ask, can the University of Oxford imagine itself as a safe space for mobilising imagination for healing across cultures and boundaries, with the Pitt Rivers as the fulcrum? First Words Good afternoon, I begin by acknowledging and paying my respects to the elders and leaders of the University of Oxford and the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM), and to the distinguished guests for graciously responding to our invitation to be part of this public event. Thank you all for standing here with us, the Naga delegation, and being part of this historic step in our shared journey towards a future of healing and wholeness. To this dignified assembly, I extend warm greetings on behalf of the Reverend Dr. Wati Aier, Convenor and all the members of the Forum for Naga Reconciliation, the Naga Tribe Hohos and the Recover Restore and Decolonise team. And on behalf of the Naga delegation, I express our deepest gratitude to the Pitt Rivers Museum, Director Dr Laura van Broekhoven and the team, for facilitating the space and enabling a robust process of cultivating and nurturing democratic engagement. Now, we can reimagine together the Naga repatriation process through the lens of healing, reconciliation, justice and decolonisation. As you know, the Naga Delegation travelled across the blue waters, from the Naga Hills to this historic institution. This past week has been momentous. We wrestled with the burdens of history and imagined the possibilities of the future. For the first time in over more than a hundred years a Naga delegation led by elders reconnected with our ancestors. One of our leaders, Thejao Vihinuo, President of the Angami Public Organisation, echoed the Naga sentiments during the Opening Session on June 9 when he said, ‘As we come to visit the remains of our ancestors, our hearts are filled with grief, and we are in anguish for the humiliation that our ancestors were subjected to even after death. But we take comfort in the fact that these remains of our ancestors have stood here in Pitt Rivers Museum for many years, silently proclaiming the history of the Nagas.’ He adds, ‘if you can see the remains of our ancestors as we are doing here today and acknowledge the history they speak of, this process of repatriation will go a long way in healing the wounds of all people involved.’ It is in this spirit that we participated in meaningful conversations and dialogues, insights and reflections as we closely examined the return process and the way forward. We remain grateful to all those who have extended their acts of solidarity and friendship throughout this time. Allow me to introduce the members of this delegation: I request the Elders and Leaders of the Naga Tribe Hohos, who represent the voice of the people to please stand where they are and as they remain standing, I call the members of the Forum for Naga Reconciliation, who have been working for the healing and reconciliation of the Naga people to stand. Now Recover, Restore and Decolonise, the young voices who are engaging with the Naga communities on the question of repatriation, please stand. This is the Naga delegation. I invite the Nagas living in the UK and elsewhere to also stand with the Naga delegation. I now invite all those who have worked or been associated with Nagas to stand with us in solidarity. I now request all those seated to please stand with us in the spirit of a shared humanity. I urge all of you to move around shake hands to greet each other. Thank you. I pay my respects to my elders and leaders past, present and emerging. The Beginning In the second half of 2020, when the world was still reeling from the impact of the COVID-19 and learning to cope with the pandemic-induced lockdown, Professor Dolly Kikon shared with FNR the PRM’s initiatives with different communities to return ancestral human remains taken during the British colonial period. After some back and forth discussions, the FNR had its first meeting – via zoom with the PRM on November 3, 2020, which Professor Dolly Kikon and Professor Arkotong Longkumer were a part of. The initial discussions focused on examining issues together around colonial violence and repatriation of ancestral remains, the processes and procedures involved, and its intersection with reconciliation, healing and decolonisation. This led to an internal dialogue within the FNR, before reaching out to the Naga people. In his Discourse on Colonialism, Aimé Césaire points out that, ‘Museums are only possible when one culture systematically steals the creations of others.’ The Indigenous experiences inform us that the relationship between colonial knowledge and colonial rule has been central to the process of one culture consuming and digesting the other. Indeed, for Indigenous Peoples, museums have been symbols which represent ideas of victor’s justice, might is right and survival of the fittest. Ultimately, they became the keepers and storehouses of colonial knowledge from the cultural other. While mindfully aware of this historical perspective, FNR recognises and respects the intended shift of the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Committed to Change steered by its Strategic Plan with Radical Hope to engage with communities to be part of a redressal process which includes ‘social healing, and the mending of historically difficult relationships through collaborations which involve listening, learning and inspiring creativity.’ It says, ‘By unearthing and undoing through redress, we aim to work together to reimagine these museums as spaces in which reconciliation might be able to come about.’ Intrigued by this encouraging initiative about Radical Hope, FNR reciprocated by agreeing to facilitate a journey of internal reflection and community engagement to elicit a Naga response regarding the ‘future care and/or return’ of Naga ancestral human remains currently stored in the museum. Recognising the need for a Naga-led process that is inclusive, participatory, and collaborative, the FNR reached out to Naga organisations. One of FNR’s predicaments was the fact that many Nagas were unaware that their ancestors were displayed for decades in museums at the PRM and other European museums. Since people were only beginning to learn about this, the initial reactions were diverse. Critical questions were raised about the relevance and timing of engaging with repatriation when the Naga people were embroiled with pressing issues affecting the quality of daily life. Some questioned whether FNR was the appropriate Forum to be even involved, let alone facilitate this process. From the outset, the Forum for Naga Reconciliation was clear that it would serve as a facilitator to seek the Naga people’s consent, participation and active support, specifically from the Naga tribe hohos, the Churches, civil society and members of the public. After all, the people alone will determine the future status and care of the Naga ancestral remains. The process generated cautious optimism which focused on engaging with communities by creating awareness, addressing fears and assumptions, confronting colonial stereotypes and labelling, and exploring how to take this journey forward. The incremental process generated a spectrum of intergenerational responses based on their experiences. Generally, the younger generation were more open and enthusiastic with an opportunity to be rooted in their stories and culture. One the other hand, the older generation were more deliberate and raised broader questions around historical injustices and trauma, the legacy of colonialism, the need for accountability coupled with the politics of apology. All these creative tensions heightened the public need for more detailed information, not just about repatriation and the procedures involved, but also provenance, description, the nature and context through which the remains were acquired and taken away, and by whom. The Why and How became important points of public discourse. These questions highlighted the need to have a dedicated team of volunteers that would begin designing and guiding the process along with the communities. Consequently, FNR formed the Recover, Restore and Decolonise (RRaD) team. Their methodology is based on a participatory action research design with Naga communities which is generating public awareness, strengthening networks and developing a Naga response, an evidence-based case, to the repatriation of ancestral human remains. The RRaD team has been instrumental in strengthening the process from the ground up, as well as nurturing critical solidarity and partnerships with fellow Indigenous Peoples involved in recovery of ancestral remains and decolonisation. Reverend Dr. Ellen Konyak, the Coordinator of the RRaD team, will be sharing with you in greater detail their experiences and learning. However, allow me to refer to three reflections that are interweaving and shaping the emerging narrative.

In the September Dialogue 2024 on Repatriation, Decolonisation and Healing, Dr Wati says, ‘Repatriation, then, is the process of re-establishing relationships and building a community of nations after a long duration of silence. It offers Nagas the chance to talk about the history of colonialism and its power, mourn the dead, and reconcile with the past in an effort to muster truth and justice.’ He goes on to say that “we must allow ourselves to discuss the colonial past and our hurts and how we can move on with confidence in constructively pursuing our historical and political de facto.’ All these reflections indicate the in-depth contemplative process taking place with the growing awareness of Naga ancestral remains. As much as the process has been about learning, it has also been about unlearning and truth-telling. It is opening spaces for individuals and communities to imagine anew and recognise the importance of self-definition because colonial knowledge continues to negatively impact by creating and perpetuating stereotypical images and prejudices. When the concept of repatriation was new to the Naga consciousness, the discussions tended to converge around the outcome and the status of the human remains, rather than on the process itself. Today, the dialogue process is peeling away the many layers as a new realisation dawn that many of the ancestral human remains and cultural objects were taken without people’s knowledge and consent. This is opening the space for a fresh understanding of the impact of the colonial era, and how it contributed towards cultural displacements that took place in the various Naga village republics. Repatriation is not only about returning ancestral human remains, but of creating a new narrative in partnership, as well as thinking and interacting differently. The emerging imagination points to the need for a multi-layered and interdisciplinary approach within the framework of humanisation, which involves restoring a peoples’ dignity and respect. This requires transformative thinking and offering alternative paradigms to address historical trauma and ongoing injustices through restorative justice and healing. A Journey Towards Healing For Indigenous Peoples like the Nagas, with a long history of conflict, we are constantly searching for solutions to our problems, rebuilding our communities from the historical trauma of conflict and violence, and engaging in the praxis of reconciliation to heal the brokenness. If we can pause this moment and look at the increasing cycles of violence, fragmentation and polarization in the world today, can we ask ourselves what does it mean to dream and imagine again? Our current inability to constructively address the burdens of history continues to define everyday life and obstructs the way forward. It is far easier to reinforce uncertainties and widen differences rather than reconnect and rebuild relationships that strengthen peaceful coexistence and harmony. I think of the Naga hearth made of three stones. Each of these stones represents a different role and they serve as a platform to create space for the fire to burn where fuel and oxygen meet. Each of these stones needs to be the same height and planted firmly on the ground so that the pot resting on it is balanced. If one of the stones is taller than the other two, the pot will be unstable. Today, let us imagine that the three stones are: Humanisation, JustPeace and Healing, the embodied aspirations of many people. Can our combined imaginations be the means for the stones to interact and cooperate to create energy? Healing for Indigenous Peoples is central when addressing the historical trauma transferred from generation to generation. It provides them with an opportunity to move beyond their pervasive sense of victimhood caused by colonisation, exploitation, militarisation, including loss of land, spirituality, and culture. But it does not end there, the process needs to also include those responsible for their dehumanising condition. Winona LaDuke, while speaking On Redemption says, ‘the perpetrators also carry the weight of the crime and becomes his own victim … in that the perpetrator’s guilt is not healthy either.’ So, ‘the process of apology and redemption, or forgiveness,’ she points out, “is a mutual healing process.’ To enable mutual healing, Indigenous Peoples need to address their own hurts and allow healing to take place so that they can enter a process with the perpetrators of injustice on their own free will. This is the basic premise of restorative justice. The Naga people are aware that both internal and external factors are essential to address inner divisions, and the historical injustices caused from the outside. FNR convenor Dr Wati Aier emphasizes that, ‘Somewhere in the repatriation process, acknowledgment of historical injustices, hurts, and anger must occupy an important moment for addressing past wrongs to arrive at reconciliation.’ He says, ‘Repatriation involves a willing sender and a willing receiver, and as both parties commit to the process of repatriation, both groups involved must prudently review their own history and envision their future.’ Contextually, Dr Wati emphasizes that, ‘reconciliation between the willing sender and the willing receiver must work for the removal of socio-cultural-politico contradictions of the historical past. Reconciliation is not achieved by simply having the ancestral human remains return home, but more importantly through the triumph over the old and the hope of new beginnings.’ In this way, we find creative, imaginative and relevant means to transcend static goals. The Naga engagement with the world is constantly evolving with growing awareness, connections and interactions, particularly in an era of technological expansion. And we ask ourselves, how do we engage with the contradictions, turbulence and possibilities of the present times. The Indigenous world is imperfect and does not claim to have the answer. But it does provide a lens that may help us to look at the world differently, to think together, and to move together in a shared language of solidarity with strength, determination and knowledge. In our attempt to understand the global discourses on concepts and processes affecting humanity, the need for Nagas to recover our values, spirituality, stories, dignity, and traditional wisdom and be makers of our own culture and future is even more urgent and relevant. This is integral in the search for a shared humanity. Without it, humans are removed from the process of humanisation. And when dehumanisation occurs, people become broken. Human experience shows us that broken relationships and power imbalances cannot lead to healing and peace. The repatriation process is creating intentional spaces with new possibilities for Nagas to question the history passed on to us by others, to take ownership by telling our stories and sharing our perspectives, to recognise the need to address the inter-generational trauma and begin the process of healing. It symbolizes the act of uncaging and beginning an intergenerational process of restoring rightful ownership and unlocking a constructive process where Naga people in our search for the emancipated self are empowered to be perpetually transforming, creating the new. In Conclusion - A Matrix Repatriation is not a straightforward linear process, nor should it be. This is because the process itself is dynamic as it deeply engages with the roots of power and relationships within the interplay of creating a safe space where the future, the past and the present meet. And, therefore, many times good intentions and complementary relationships are not sufficient, it requires vigilantly upholding the integrity and accountability of the process by all sides involved. Since our arrival, the Naga delegation has been reflecting on the progress. We believe this historic visit has given us an opportunity to broaden a substantive relationship with PRM. In this, we hope that the FNR and PRM will have the confidence to weave repatriation and reconciliation into a holistic process that is multifaceted, addresses historical injustices, heals emotional wounds, and mends broken relationships between peoples. This needs to enable a deeply transformative and decolonising process that leads to reclaiming our identities, histories, dignity, and spiritual connections after generations of historical trauma. FNR calls for a long-term committed partnership based on radical hope, trust, statesmanship, humility, sincerity and the will to agree on a strategic plan that connects and carries us into the future. We have also been reminded that in October 2015, the student-led protest movement Rhodes Must Fall tweeted that “The Pitt Rivers Museum is one of the most violent spaces in Oxford.’ And walking around the PRM and Oxford, amid history, we need to ask ourselves whether we can muster the courage to imagine – where imagination has the emancipatory capacity to create a space for humanisation where Repatriation, Healing and Decolonisation meet in harmony. So, we ask, can the University of Oxford imagine itself as a safe space for mobilising imagination for healing across cultures and boundaries, with the Pitt Rivers as the fulcrum? For Indigenous Peoples, mobilising imagination is to overcome the colonial legacies and recover their lands, their lives and their self-determining capacities where the processes of Humanisation, JustPeace and Healing meet to unlock a pathway to a shared humanity. An Indigenous leader in Asia said this notion of emancipation, ‘is based on teleological freedom – the freedom to become who we are meant to be, to be agents of justice, peace and healing.’ And yet, by implication, this process is not about glorifying Indigenous institutions, nor does it mean a total rejection of the positive values from other cultures. Rather, the process must serve as an interdisciplinary and intercultural pathway towards creating a humanising culture where all people reclaim their past, present and future. It is about setting these realities into motion by transcending the current conditions to imagine what justice, peace, healing, reconciliation, and repatriation represents to all of us. Today, this Naga delegation has come to reconnect with the ancestors and begin the process of repatriation. Today, our leaders have made a historic declaration. And therefore, when the next delegation comes, it must be to take our ancestors home and give them and the people a chance for the restless spirits to have a dignified closure and rest. Thank you for your presence here today and patiently listening! |

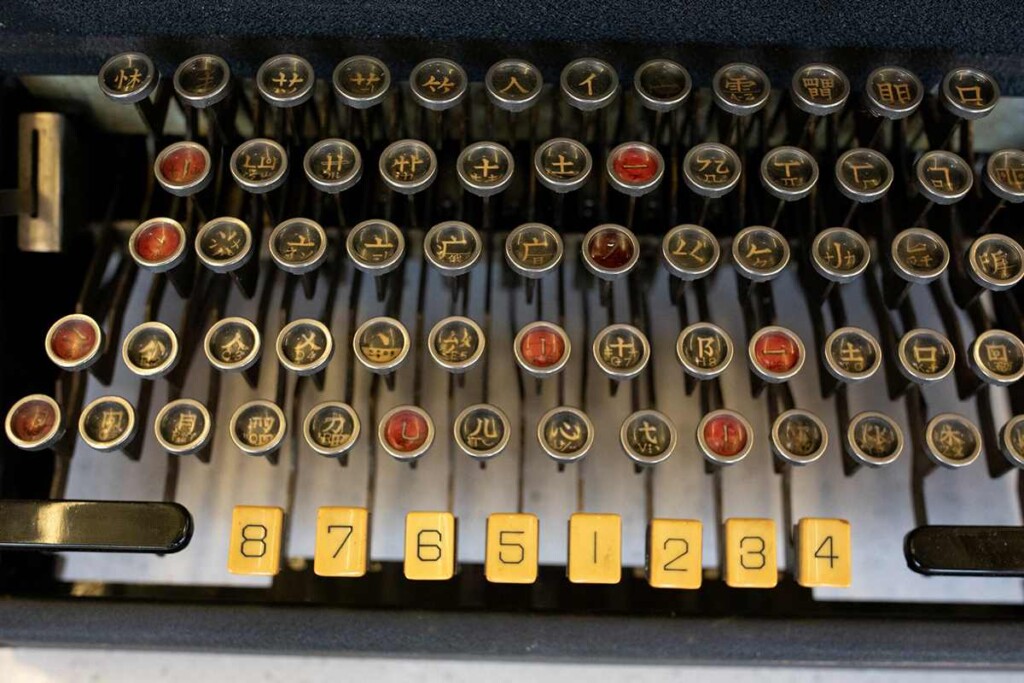

The Sole Prototype of the First Chinese Typewriter Was Discovered in a New York Basement (2025-07-02T11:22:00+05:30)

A close up of the Ming Kwai typewriter – credit Elisabeth Van Boch, supplied to GNN A Stanford scholar has been rewarded for his work documenting Chinese computing by winning his university the chance to purchase the only known prototype of the first-ever Chinese typewriter after it was found in a basement. Receiving offers through Facebook and Reddit from museums and institutions around the world, New Yorker Jennifer Felix and her husband quickly became overwhelmed and astonished by the response to their basement discovery. “Is it even worth anything? It weighs a ton!” Felix’s husband wrote along with pictures of the “Ming Kwai” typewriter. As it happened, one of the commenters pointed the couple to a book by Stanford history professor Thomas Mullaney called The Chinese Typewriter: A History. Inside, a whole chapter was dedicated to the 明快打字機 which Stanford University Press write is typically just called by the first two characters which mean “bright” and “fast”—Ming Kwai. The Ming Kwai was the first Chinese typewriter ever to include a keyboard. It was invented by Chinese-born author, translator, and cultural commentator Lin Yutang in the 1940s. The whole notion that a language with around 80,000 written characters could somehow be adapted for use in a typewriter seems bonkers. Today, writing digital text with a keyboard or phone in Chinese works by typing Western letters corresponding to the sound of the character, for example “ming” and then selecting which ming, since there are several, is needed for the text. A digital database wasn’t available in the 1940s, so incredibly, Lin created a mechanical hard drive. “The depression of keys did not result in the inscription of corresponding symbols, according to the classic what-you-type-is-what-you-get convention, but instead served as steps in the process of finding one’s desired Chinese characters from within the machine’s mechanical hard drive, and then inscribing them on the page,” Mullaney wrote in his book. The Ming Kwai’s keys contain a mixture of characters and components found in many different Chinese words. For example, in the center of the bottom row, the left-most keys between the two red ones are “er” and “xin,” both of which are characters themselves, but also can be component to larger, more complex characters. Xin, for example, means “heart” but when placed below “ni” forms the character “nin” which is a formal way to address someone. The post-war Chinese typist would depress a key in the top row, triggering a rotation in the central mechanical database that would bring a certain number of common characters into view in a part of the typewriter called the “eye”. depressing a key in the middle row would trigger a second rotation corresponding to the first, and bring up another set of characters containing both component parts, and so one to the bottom row.  History professor Thomas Mullaney and Zhaohui Xue, curator of Chinese studies examine the Ming Kwai typewriter – credit Elisabeth Van Boch, supplied to GNN History professor Thomas Mullaney and Zhaohui Xue, curator of Chinese studies examine the Ming Kwai typewriter – credit Elisabeth Van Boch, supplied to GNNWithin the “eye” lay a final selection of characters containing the components selected for on each row, and by pressing one of the numbered keys, the character would be printed onto the page. Ingenious, to say the absolute minimum. “In 1947, the Carl E. Krum Company built what is believed to be the sole prototype of Lin’s invention,” Stanford press wrote. “A year later, in debt and unable to generate interest in mass producing his machine, Lin sold the prototype and the commercial rights to the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, where Felix’s grandfather worked as a machinist.” With the help of a foundation established by two Americans of East Asian heritage, Stanford University was able to acquire the Ming Kwai and pay for its maintenance, but Mrs. Felix felt that Stanford were the most suitable custodians of the machine, since it was Mullaney’s book that helped clue her in on what it was she and her husband found in their basement.“I didn’t want this unique, one-of-a-kind piece of history to disappear again,” she said. The Sole Prototype of the First Chinese Typewriter Was Discovered in a New York Basement |

Family-Owned Vermont Ski Resort Offers the Common Man 1,200 Acres of Powder for $100 (2025-07-01T13:39:00+05:30)

Top of the lift at Bolton – credit Bolton Valley Resort, via Facebook In Vermont, a family-owned skiing business is rising to prominence as a backcountry and downhill paradise in an area and age saturated with big corporate luxury ski resorts. Just 30 minutes east of Burlington, Bolton Valley Resort trades luxury for comfort and status for friendly, powder-loving vibes. Featured in a great travel piece in the New York Times, Bolton Valley has been run by the same family for decades, finding its feet between the corporate resorts of Stowe and Sugarbush by offering skiing to the common man at an affordable price. Ralph DesLauriers, now 90 years old, opened Bolton Valley in 1966 with his father for that express purpose. Today, it’s run by his daughter Lindsay. “Skiing was a luxury sport for out-of-staters,” she told the Times’ David Goodman. “He wanted it to be accessible to Vermonters.” Along with offering cheaper passes, they installed flood light systems on the slopes to allow working Vermonters to ski after work. Every afternoon, yellow school buses disgorged students who swarmed over the 71 slopes while honing their skills, an idea of her father’s and grandfather’s that she says probably helped save the resort in the long run. That’s because nearby areas became larger and more accommodating, with bigger hotels, slopeside lodging, and hundreds of ski trails all developed at the cost of tens of millions fronted by resort conglomerates marketing for a more luxurious clientele. Bolton Valley had issues competing, and the ownership of the resort passed to the bank 31 years after its lifts first started lifting. After several new owners failed to make it profitable, locals moved in to save it—perhaps some of those who learned to ski under the floodlights. Bolton Valley Resort’s crown jewel was a 1,200-acre network of backcountry skiing trails of rare continuity. In 2011, residents learned it was going to be sold, and in opposition to that notion, worked with the Vermont Land Trust to raise $1.8 million to buy and then donate the land to the state for inclusion into Mount Mansfield State Forest with the provision that it should be kept open to backcountry skiers. In 2017, Mr. DesLauriers bought back the resort for less than what it cost him to build it half a century before. Now run by Lindsay and her brothers Evan, Adam, Eric, and Rob, it’s become a profitable venture for the first time in decades in a classic case of large corporations leaving gaps in the market to be filled by charming, alternative options. A ski pass at Bolton costs $100, around half or even a third of other East Coast ski resorts like Stowe and Sugarbush. For that price, you get six ski lifts with wait times of around 4 minutes, 1,700 feet of slopes, and nighttime skiing. Bolton is also the only place in the region that offers backcountry skiing and snowboarding, lessons, guides, and rentals all out of the same establishment.A 60-room hotel may not score big on luxury, but makes up for it with the lack of traffic jams, waiting times in restaurants and ski lifts, and parking space. Bolton Valley is included on the Indy Pass, a multi-mountain ski lift pass that includes smaller operations like Bolton. Family-Owned Vermont Ski Resort Offers the Common Man 1,200 Acres of Powder for $100 |

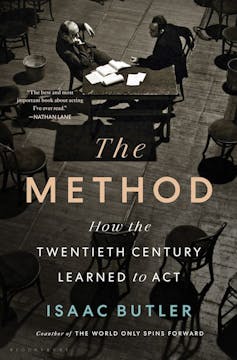

From the Moscow stage to Monroe and De Niro: how the Method defined 20th-century acting (2025-03-31T13:16:00+05:30)

|

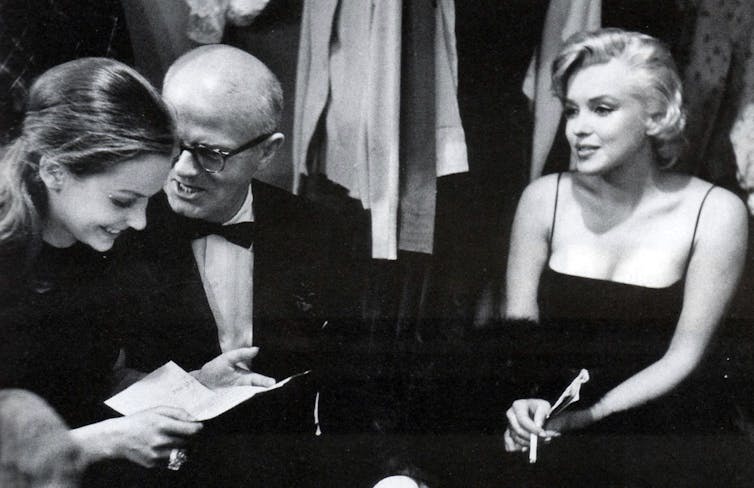

When an actor is criticised for peculiarly excessive preparation for a role, or an inability to break character off-camera, an ill-defined notion of “Method” acting (note the capital “M”) is rarely far away. Review: The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act by Isaac Butler (Bloomsbury). Living rough on the streets to prepare for a role. Abusing fellow performers to provoke an “authentic” response. Or never breaking from character throughout an entire shoot – like Daniel Day-Lewis, who supposedly insisted on being addressed as “Mr President” throughout the three-month filming of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. But while it’s easy to ridicule or parody, the Method – which casts a long shadow over European and (in particular) American acting – is complex and varied. What is Method acting?As detailed in Isaac Butler’s The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act, the Method was developed in Russia in the latter part of the 19th century.  Its creators, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislawski, transformed Russian theatre with their new approach to acting, writing and theatre production. Their system encouraged more subjective, interior approaches to performance, and more realistic, naturalistic approaches to staging. Acting had been largely externalised and action-centred, often understood in terms of preconceived gestures. The Method helped transform it into a dynamic process that unlocked deep recesses of personal experience and “emotion memory”, which could then be funnelled into a performance. It is hard to imagine modern acting without this development. Collateral damage to shooting starsThe Method is strongly linked to the new realism that emerges in New York theatre in the 1930s and 1940s, and Hollywood cinema in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s also connected to the performance styles of many of the key actors and stars of mid-century American theatre and cinema: Marlon Brando, Kim Stanley, Montgomery Clift, Anne Bancroft, Rod Steiger, Paul Newman, and many others. Its excesses and dangers are deployed as damning evidence to help explain the tragic fate of figures like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe. Shooting stars caught within the orbit of abusive Method teachers, they seemed to suffer the collateral damage of drawing on their traumatic past too deeply. The Method is often brought into debates about the distinction between performing and being, acting and reacting. But such dichotomies are unhelpful in understanding the complex interior, exterior and collaborative processes at play in any great performance. This is particularly true for film acting, a mode of performance that requires actors to register minute changes of expression, small actions and gestures – all of which are then blown up in microscopic detail.  Anne Bancroft is a key mid-century actor whose performance style is linked to the Method. She’s pictured (right) with Dustin Hoffman, another famous Method actor, in The Graduate. IMDB Anne Bancroft is a key mid-century actor whose performance style is linked to the Method. She’s pictured (right) with Dustin Hoffman, another famous Method actor, in The Graduate. IMDBAs James Harvey has claimed, the art of acting for the camera in the 20th century is largely a matter, for the spectator, of “watching them be”. In some ways, the Method, which at its base foregrounds individual agency and psychology, is brilliantly suited to self-centred notions of both society and art. And to the curious alchemy that fuses actor, celebrity and character in star-centred theatre and cinema. It is unsurprising that this often mannered style reached its peak of fame in the 1950s, an era of rising individualism. It rocketed to ascendancy alongside Abstract Expressionism in American painting, stream of consciousness in various forms of writing (such as the work of the Beats), and in the improvisational modes of jazz favoured by artists like Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman. Revolution, individualism and FreudIsaac Butler’s book is a fascinatingly detailed, brilliantly readable and often compelling account of the hundred-year journey of the Method from pre-revolutionary Russia to the stages of New York – and the rise of New Hollywood and actors like Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Ellen Burstyn.  Method actor Al Pacino and Lee Strasberg, famous Method acting teacher (and actor), in The Godfather II, as Michael Coreleone and Hyman Roth. IMDB Method actor Al Pacino and Lee Strasberg, famous Method acting teacher (and actor), in The Godfather II, as Michael Coreleone and Hyman Roth. IMDBIt is not shy in exploring the complexities of this journey and the many offshoots and variations produced along the way. Butler examines the social, cultural and political implications of the evolving and splintering Method system, and how it responded to various forces. These include: proletarian demands, the Russian revolution, the rise of leftist politics in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, Freudian psychology, the increased individualism of post-war America, and the anti-communist blacklist. And, of course, there was the Method’s ultimate canonisation and popular recognition in plays and films like A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, and Marty. Butler also meticulously introduces and describes the first-tier actors and directors of the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s who proclaimed (and in some cases denied) the Method’s direct influence and legacy. For a significant period in the 1960s and 1970s, with the increasing celebrity of prominent acting teachers of the Method like Lee Strasberg (of the Actors Studio) and Stella Adler, the Method’s various offshoots could claim true cultural dominance. The influence and fiery disagreements of these teachers are a focus of Butler’s book. Butler details Marilyn Monroe’s increasingly close and personal relationship with Strasberg (and his relationship with second wife Paula, Monroe’s acting coach) and the influential patronage of actors like James Dean, Montgomery Clift and Rod Steiger. He also describes truly terrifying classes and feedback sessions conducted by Strasberg at the Actors Studio.  Method acting coach Lee Strasberg (centre) with actor daughter Susan Strasberg (left) and famous student Marilyn Monroe (right). Laura Loveday/Flickr, CC BY Method acting coach Lee Strasberg (centre) with actor daughter Susan Strasberg (left) and famous student Marilyn Monroe (right). Laura Loveday/Flickr, CC BYIn contrast, Adler insisted on an approach to acting that stuck more closely to Stanislawski’s original concept of “emotion memory”, and recommended extensive processes of research and preparation in the creation of any performance. Among her most significant students were Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Elaine Stritch and Warren Beatty. A particular strength of Butler’s cultural history is how he carefully plots this rise, while granting equal space to each stage of the journey. His book is, nevertheless, a little too focused on the impact of the ideas of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislavski on the stages and screens of Russia and then the United States. There is little sense of the impact of these ideas elsewhere in Europe, and British acting is mainly used as a counterweight, put forward as a haven for a more exterior form of acting, epitomised by the work of Laurence Olivier (who famously scorned Method acting). Butler also provides accounts of writers important to the Method. Anton Chekhov, central to the initial work of the seminal Moscow Open Art Theatre, is a key source throughout. And he charts the contributions of Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin and Paddy Chayefsky, who were equally integral to various stages of the Method’s development, dissemination and devolution.  Tennessee Williams was one of the writers integral to various stages of the Method’s development. He’d pictured here (third from left), with Truman Capote (second from left). From the Key West Art and Historical Society. Florida Keys Public Library/Flickr, CC BY Tennessee Williams was one of the writers integral to various stages of the Method’s development. He’d pictured here (third from left), with Truman Capote (second from left). From the Key West Art and Historical Society. Florida Keys Public Library/Flickr, CC BYThe book gives space to the competing approaches of writers and directors like Bertolt Brecht and Vsevolod Meyerhold, along with the more varied approaches of actors like Meryl Streep. Its compelling chronological narrative ends up focusing, however, on a judicious selection of key figures within the US and Russia. As Butler documents, the outcomes of this change – though he is also careful to note the seeds of this style even earlier and elsewhere – could be truly astounding or monumentally disastrous. Triumphs, failures and major playersAmong the pleasures of Butler’s book is how it documents these triumphs and failures – sometimes within the performance of the same play by a single company, as in the case of the Actors Studio’s staging of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. He also provides evocative portraits of many key figures like Elia Kazan, Maria Ouspenskaya, Howard Clurman, Richard Boleslavsky and John Garfield. He focuses on people who were particularly important in managing entities such as the American Laboratory Theatre, the Actors Studio, the Group Theatre and the Moscow Art Theatre, directing breakthrough films and plays (the duplicitous Kazan emerges as a titan in this regard), writing accounts of how the “system” worked, or introducing new styles of acting.  Konstantin Stanislawski. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY Konstantin Stanislawski. Wikimedia Commons, CC BYAs in many books of this kind, such a focus and approach is also a limitation. This is a cultural history less concerned with the nuts and bolts of theatre and film production – though it is often incisive in this department and is plainly written by someone with a deep knowledge of these processes – than the collaborations and conflicts between figures adapting and transforming Stanislavski’s initial “system”. This, of course, also makes this very well-written and carefully organised book a true pleasure to read. Butler provides a convincing account of the Method’s importance in the history of ideas. He doesn’t shy away from arguing for the decreased currency of many of its techniques and lessons, but make claims for its ongoing influence alongside a range of other approaches and methods. He provides a complex account of The Method’s various forms and variations across almost 150 years. He also provides important cultural and social context for helping understand why a shift to a more “realist” or personal, self-centred form of acting was both hard fought for and inevitable. Even a simple thing like the improved lighting in theatres from the late 19th century had a profound impact on what was possible in terms of more interior and subtle forms of staging and performance. This was, of course, amplified in the rise of sound cinema in the late 1920s and its more tempered forms of screen acting that led to the minimalist styles of stars like Gary Cooper, Clint Eastwood and Juliette Binoche. Popular accounts of the Method’s legacy tend to steer towards trivial excesses, like Jared Leto allegedly sending his co-stars various “gifts” like used condoms in preparation for his role as the Joker in Suicide Squad. (Which, for the record, Leto now denies.) But Butler’s book makes convincing claims for why we should continue to take this approach and its legacy seriously. In so doing, it answers its pointed epigraph from Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: “We’re actors. We’re the opposite of people.” If this magisterial book does little else, it certainly convinces the reader that nothing could be further from the truth. Adrian Danks, Associate professor in Cinema and Media Studies, RMIT University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

The tricky notion of ‘value’ in the arts (2025-02-13T12:33:00+05:30)

|

There’s plenty of discussion about arts funding in Australia – but are we ready to tackle tough questions around the “value” of the arts? That’s a challenge that will involve scrutinising the “benefits” delivered by arts programs and rethinking some of our ideas about impact. Recently these questions have been framed in terms of measurement – a phenomenon that has to do with an increased emphasis on what is termed the “creative” or “cultural” industries. Welcome to the arts industryGovernments and policy makers concerned with the allocation of scarce resources, and with the demise of traditional economic drivers for development, have turned to these sectors as areas of potential growth. The word “industry” nicely moves the whole area away from anything “non-productive”. This framing of the arts as an industry has fuelled the sometimes strident debate over funding models for the arts, particularly when a funding cut has taken place. Yet for better or worse, the arts and related cultural phenomena represent activities that now have value and benefits for government – so there will be policy delivered upon art producers regardless of the debate. The key issues for all is defining and measuring all the possible permutations of value. Intrinsic and instrumental benefitsSome clarification is possible if we separate instrumental benefits from intrinsic benefits. Instrumental benefits are those that pertain to social, economic or policy outcomes. An outcome of a community-based theatre production might be to involve disadvantaged sectors of the community, thereby increasing social inclusion. Similarly, a sculpture trail might be established in an economically-depressed region, with the aim of increasing local employment. Such benefits are increasingly cited in the conversations surrounding the impact of the arts. The intrinsic benefits of the arts are less obvious. While not being ignored by arts organisations, and of interest to many artists, the “impact” of art on an individual, a community or on society is a nebulous concept. How did the art resonate with the viewer? Was the community intellectually stimulated? Did the art make a lasting impression? Did it increase social bonding? Much of the policy work done on measuring intrinsic impact is done in the performing arts. Theatre, opera and music companies have a particular interest in measuring intrinsic impact, as their revenue streams rely on a paying audience, and indeed one that returns for future performances. Intrinsic impact factors such as audience engagement and stimulation are part of the concept of “artistic vibrancy” that the Australia Council uses as a criterion in its Artistic Reflection Kit for arts organisations. Did the art make a difference?There is little to guide us in understanding such issues in a broader arts context. Certainly museums and galleries, as well as major events such as the Biennale of Sydney undertake visitor surveys. But their findings are frequently framed in relation to audience development or marketing strategy. Engagement sometimes simply means: how many people went, and where were they from? While this sort of information is vital in a world where competition for the cultural tourist is fierce, it does not assist us in understanding the basic question of whether the art, in whatever form, made a “difference” to those that viewed it (however that may be defined) and how that might be considered a “value”. Of course, it can be argued such a question is irrelevant in an artistic sense. Many see any measurement of artistic value as further evidence of the commodification of art. Art producers frequently reject the materialistic concept of “product” being applied to their creative output, and clearly consumer demand is not generally the primary driving force behind art and other cultural-based production. Product-driven artistsEven so, artists do need to be product-driven. If they are not they risk their artistic integrity, the very thing that challenges their audiences. This means that conventional techniques to “sell” artistic production do not necessarily work. For any exhibitor of challenging art this is a common problem. Do you keep churning out those room-filling blockbuster exhibitions – or curate something that your audience might potentially not actually like? Perhaps splitting value into instrumental benefits and intrinsic benefits is actually unhelpful because it artificially separates the individual/ community/ emotional from the policy/ economic. By this I mean that if a concert does not engage and resonate with visitors by having some intrinsic value, then any other subsequent instrumental benefit simply does not flow on. In other words, if the audience does not like the art, they will not “consume” it (buy, view, etc.). Art for individuals and communitiesFor me, taking such an holistic view of artistic endeavours recognises that there is an interconnectedness between individual benefits and societal benefits that is indeed important. What benefits the individual may well benefit that individual’s community – and vice versa. Does this make impact any easier to measure? Or value any easier to define? Perhaps not immediately. But it does provide an alternative way of conceptualising value in the arts, one that may be used to reframe a debate that tends to be weighted toward measuring instrumental benefits. It’s not just that funding bodies find it easier to measure instrumental benefits, it’s that the intrinsic value of art is, by its very nature, difficult to measure. How do you measure intellectual stimulation? Emotional engagement? Joy? Sure, there is research conducted in these areas, but it is not finding its way into the debate over the value of the arts. And until it does the arts will continue to be valued more for its role as a driver of economic development than as a cure for the soul – or worse still, not valued at all. Further reading: Kim Lehman, Lecturer in Marketing, Tasmanian School of Business and Economics, University of Tasmania This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What is the point of assessment in higher education anyway? (2025-02-03T13:51:00+05:30)

The recent decision to ban multiple-choice questions at an Australian university has sparked debate about the purpose of assessment in higher education. While there are many problems with the ways in which multiple-choice questions are used in universities, the problems with the inauthentic nature of multiple-choice questions could similarly be levelled at most forms of assessment. Assessment has traditionally been seen as a way of comparing the performance of students during and at the end of semester. While there are criticisms of this way of looking at assessment, what is actually being measured in this process is another big question. Assessment of recollectionTraditionally, assessment has been conducted in higher education to test whether students can recall content. While a base level of factual information is needed before moving on to types of higher-level thinking required of experts and professionals, remembering is not enough. As I have discussed previously, the ubiquitous availability of information on our smart phones and across our 3G networks means just remembering something isn’t enough anymore. We need to know how to evaluate the information. If we are really going to be honest about this, unless graduates are constantly using the information, the majority of people usually remember only isolated facts from their undergraduate degrees several years later. This was best exemplified by Father Guido Sarducci’s humorous notion of the Five-Minute University. This is where, for example, you could be taught in five minutes everything you will remember about economics five years after graduation. Assessment of thinkingA better aim for higher education assessment is to attempt to get at students’ thinking processes. It is possible to get some sense of how students arrived at an answer by asking them to provide a written response rather than allow them to pick (possibly at random or via semi-educated guess) from a set of pre-defined options. The same logic is at play here as when students are asked to show their working as part of a maths problem. No matter how much students are asked to write, one thing remains consistent: the best that assessors can do is hope students are thinking about issues and concepts in appropriate ways. It is not possible to measure thinking, so no matter what method is used, some element of judgement by the assessor is required. Moving away from multiple-choice questions therefore does not necessarily mean that it is easier to tell what students are thinking. Assessment for learningA more recent notion is the idea that assessment can be for learning rather than just conducting assessment of learning. As discussed elsewhere, the testing effect provides strong evidence for the enhancement of learning through exams. This is based on the same principle as flash cards - that we put what we think we know and remember through some sort of test to assist with encoding it into long-term memory. Broadly, the notion that learning is enhanced through the testing of knowledge makes intuitive sense in practice settings and is supported by laboratory-based research. Much of the evidence for the testing effect has been gathered through the use of multiple-choice questions so it would appear that this format could be good for learning. Assessment of student becomingWhen considering the purpose of a university education at the most fundamental level, it isn’t just about remembering or thinking. The ultimate aim of university education as it has been historically conceived is a process of becoming. Students come to university so that they can become lawyers, architects, historians and scholars with all the associated cognitive skills. While this process of becoming is at the core of the purpose of university education, it is nonetheless difficult to assess. The very definition of becoming is about subjective experience and not an objective reality that can be easily quantified in some way.

This notion of becoming is particularly hard to get at with a bank of multiple-choice questions. That may have led in part to their continued derision as an assessment approach. What is really being measured?Assessment tasks completed by students are not precise psychometric tools that can give teachers deep insights into the ways that students think or who they are becoming. At best, assessment tasks can be designed to give a teacher a reasonable chance of using their expert judgement to determine whether students have met the intended learning outcomes. In order for this judgement to become more valid and reliable, it is not just the questions asked of students but the curriculum as a whole that needs to be considered. If a teacher is relying on a multiple-choice exam at the end of semester to give some inkling about what their students are thinking and who they are becoming, there is something fundamentally wrong with the way the entire subject/unit is designed. A well-designed subject will give a teacher many opportunities to observe the progress of their students. This can be challenging with very large groups of students but it can be done through the use of effective learning design. Ultimately, prohibiting one type of exam question is only dealing with a symptom. Until teachers move away from the notion that university education is about remembering things and start designing entire subjects and degree programs that address thinking and becoming, the problems observed with the types of assessment used will persist. Jason M Lodge, Research Fellow, Science of Learning Research Centre & Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |