L. Jamila Haider, Stockholm University and Steven J Lade, Stockholm UniversityAccording to the OECD, development aid recently reached a new peak of $US142.6 billion a year. But international assistance that aims to alleviate poverty can have undesirable, and often unintended consequences on both nature and culture. And how to alleviate poverty without degrading the environment and cultural values remains a significant global challenge. Trapped in our thinkingIn a new review paper in the journal Science Advances, we call into question a cornerstone of development aid: the “poverty trap” and its “big push” solution. The poverty trap is a concept widely used to describe situations in which poverty persists under a certain asset threshold through self-maintaining mechanisms. In other words, it’s the vicious cycle of poverty, where the poor get poorer because they cannot accumulate savings or have enough energy to work. The term, which was used by both Jeffrey Sachs and Paul Collier in 2005 to describe households or countries stuck in low-levels of economic well-being, was central to the UN’s Millennium Development Goals. The “big push” – one of the earliest theories of development economics – is a still-popular one-size-fits-all approach to alleviating poverty at community and household levels, despite its known limitations. The basic idea of this theory is that it takes a big coordinated push of investment to allow economies to take off beyond a critical point (as defined by the poverty trap). The two concepts, as you can see, go hand in hand. But there’s an issue: though the poverty trap is a prominent way to conceptualise persistent poverty, its strictly economic view of poverty has thus far ignored the roles of nature and culture. With 78% of the world’s poorest people living in rural areas, development aid is often targeted at financial and technological farming solutions. Development agencies encourage farmers to grow single cash crops, or monocultures, such as genetically modified cotton in India, that they can sell to rise out of poverty. This strategy has had mixed results and, in some cases, serious ecological and social consequences that can reinforce poverty. Modelling alleviation strategiesIn our paper, we provide a way to extend poverty-trap thinking to more fully include the links between financial well-being, nature and culture. Our new approach identifies three types of solutions to alleviate poverty. The first is the so-called standard “big push”, to tip countries “over the barrier” so they have better-functioning economies. The second is to lower the barrier. And this could include everything from training farmers to changing behaviour and practices. These two classifications form the backbone of current aid strategies. But we introduce a third classification, which we call transforming the system, with the goal of rethinking the traditional intervention strategy. Using theoretical multi-dimensional models of different relationships between poverty and the environment at the household or community levels, we tested the effectiveness of these poverty alleviation strategies. For example, a popular and empirically supported narrative is that poor people degrade their environment, but less well-known empirical evidence shows how poor people do not disproportionately deteriorate the environment. They are often stewards of nature and create and maintain features such as agricultural biodiversity. Take for example, the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan and Afghanistan, which are characterised by high biological and cultural (aka biocultural) diversity. In a context like this, people may be poor in monetary terms but care for an incredible diversity of agricultural crops with their rich ecological knowledge and cultural practices. And the diversity of traditional seeds may, in turn, help make them resilient at a regional level to shocks. In such places, the conventional push “over the barrier” to increase food production (through improved seeds or fertilisers) may risk losing biodiversity or traditional knowledge. Our models show how a transformation strategy in which endogenous actions change the status quo could in some contexts alleviate poverty without serious consequences for nature and culture. This possibility creates space for currently underrepresented narratives of development, such as agro-ecology or food sovereignty. Transformative changeThe results of the models show that conventional development interventions that ignore nature and culture can reinforce poverty; transformative change may be necessary in those contexts; and asset inputs may be effective in others. These results are synthesised in the “poverty cube”, which shows how we brought together the multi-dimensionality of poverty, different intervention pathways and diverse contexts. Our approach to poverty traps may be useful for people in the development field to think through the implications of diverse development trajectories. Prior to our multi-dimensional poverty cube, poverty-trap models usually considered only the monetary dimension of being poor. Now, development actors can more easily envisage the consequences of different alleviation strategies on not just economic well-being but also on nature and culture – and how they interact. The framework we developed may be useful for categorising interventions and their consequences on nature and culture across different sectors. An interdisciplinary endeavourThe paper emerged from a number of years of collaboration between a theoretical physicist, sustainability scientists, and an economist. It involved a highly interdisciplinary research approach. The importance of biophysical and cultural settings for poverty alleviation has long been understood. But interventions continue to be designed based on the poverty trap, a concept that usually neglects these factors. Our poverty cube could help donor agencies better integrate poverty, environment and culture in their thinking and development planning. Integrating these factors will be a major challenge for the Sustainable Development Goals. What we need to do next is dig deeper into understanding how this type of dynamic multidimensional modelling can be used in place-based studies aimed at communities. L. Jamila Haider, PhD candidate, Sustainability Science , Stockholm University and Steven J Lade, Researcher in resilience of social-ecological systems, Stockholm University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Innovative New 'Sponge' Park Helped Save Historic Atlanta Neighborhood from Flooding (2025-09-30T11:50:00+05:30)

Rodney Cook Sr. Park in Vine City – credit, HDR inc. Rodney Cook Sr. Park in Vine City – credit, HDR inc.$40 million may seem like a lot of money to the average person, but it’s just a fraction of what municipalities were spending to cleanup and shore-up their cities and towns following Hurricane Helene. For Vine City, Atlanta, $40 million was the cost of a solution to flooding problems that long predate Helene. It bought the historic neighborhood a big, beautiful new park that works like a sponge. GNN has reported on the “sponge city” concept before, whereby parks and urban developers use greenery and water features to help absorb rain and floodwater to slow its entry into the drainage system. It’s been picked up by the Netherlands and China, and now too, in Atlanta with Rodney Cook Sr. Park. Atlanta City Council member Byron Amos, who was born and raised in Vine City, remembers several flooding events that left residents’ basements submerged and cars soaked through. Amos worked with the Trust for Public Land to adopt the sponge city concept for Vine City. “When water is rerouted through the neighborhood to this site, the pond fills up, and the rain gardens, other green infrastructure throughout the park houses water to be collected and basically take the load off the city’s stormwater system,” said Jay Wozniak with the trust. Despite being 300 miles inland, Helene reached out her stormy fingers even as far as Atlanta, and suddenly, Amos and Woziank’s solution would be put to the test. “People were calling, ‘The park is flooding! The park is flooding!’ and my response was, ‘It’s doing its job,” Amos told CBS News. Indeed, Rodney Cook Park filled up with 9 million gallons of water, but nearby residents’ homes stayed dry. Within 72 hours, Wozniak said, no one even knew a storm had taken place. In addition to being a piece of the stormwater system, the park is also a beautiful gathering space filled with water features, a multi-sport composite court, plenty of green spaces, and fitness equipment.Built for the trust by HDR, it collected no less than 10 major architecture, design, and landscape engineering awards. Innovative New 'Sponge' Park Helped Save Historic Atlanta Neighborhood from Flooding WATCH the story below from CBS… |

This Startup Is Using Dead Leaves to Make Paper Without Cutting Trees (2025-08-26T11:22:00+05:30)

credit – Releaf Bags credit – Releaf Bags26-08-2025, Businesses like to talk about the concept of a closed loop or circular economy, but often they’re trying to close small loops. Releaf Paper takes dead leaves from city trees and turns them into paper for bags, office supplies, and more—which is to say they are striving to close one heck of a big loop. How big? Six billion trees are cut down every year for paper products according to the WWF, producing everything from toilet paper to Amazon boxes to the latest best-selling novels. Meanwhile, the average city produces 8,000 metric tons of leaves every year which clog gutters and sewers, and have to be collected, composted, burned, or dumped in landfills. In other words, huge supply and huge demand, but Releaf Paper is making cracking progress. They already produce 3 million paper carrier bags per year from 5,000 metric tons of leaves from their headquarters in Paris. Joining forces with landscapers in sites across Europe, thousands of tonnes of leaves arrive at their facility where a low-water, zero-sulfur/chlorine production process sees the company create paper with much smaller water and carbon footprints. It is said of the city of Kyiv that one can walk from one side to the other without ever leaving the shade of horse chestnut trees. Whether Ukrainian founders Alexander Sobolenko or Valentyn Frechka of Releaf Paper ever lived or worked in Kyiv, perhaps this preponderance of greenery influenced their thinking while the pair were coming up with the idea in university. “In a city, it’s a green waste that should be collected. Really, it’s a good solution because we are keeping the balance—we get fiber for making paper and return lignin as a semi-fertilizer for the cities to fertilize the gardens or the trees. So it’s like a win-win model,” Frechka, co-founder and CTO of Releaf Paper, told Euronews. Releaf is already selling products to LVMH, BNP Paribas, Logitech, Samsung, and various other big companies. In the coming years, Frechka and Sobolenka also plan to further increase their production capacity by opening more plants in other countries. If the process is cost-efficient, there’s no reason there shouldn’t be a paper mill of this kind in every city. “We want to expand this idea all around the world. At the end, our vision is that the technology of making paper from fallen leaves should be accessible on all continents,” Sobolenka notes, according to ZME Science. This Startup Is Using Dead Leaves to Make Paper Without Cutting Trees |

Underground nuclear tests are hard to detect. A new method can spot them 99% of the time (2025-06-12T11:49:00+05:30)

Since the first detonation of an atomic bomb in 1945, more than 2,000 nuclear weapons tests have been conducted by eight countries: the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea. Groups such as the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization are constantly on the lookout for new tests. However, for reasons of safety and secrecy, modern nuclear tests are carried out underground – which makes them difficult to detect. Often, the only indication they have occurred is from the seismic waves they generate. In a paper published in Geophysical Journal International, my colleagues and I have developed a way to distinguish between underground nuclear tests and natural earthquakes with around 99% accuracy. FalloutThe invention of nuclear weapons sparked an international arms race, as the Soviet Union, the UK and France developed and tested increasingly larger and more sophisticated devices in an attempt to keep up with the US. Many early tests caused serious environmental and societal damage. For example, the US’s 1954 Castle Bravo test, conducted in secret at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, delivered large volumes of radioactive fallout to several nearby islands and their inhabitants. Between 1952 and 1957, the UK conducted several tests in Australia, scattering long-lived radioactive material over wide areas of South Australian bushland, with devastating consequences for local Indigenous communities. In 1963, the US, the UK and the USSR agreed to carry out future tests underground to limit fallout. Nevertheless, testing continued unabated as China, India, Pakistan and North Korea also entered the fray over the following decades. How to spot an atom bombDuring this period there were substantial international efforts to figure out how to monitor nuclear testing. The competitive nature of weapons development means much research and testing is conducted in secret. Groups such as the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization today run global networks of instruments specifically designed to identify any potential tests. These include:

A needle in a haystackSeismometers are designed to measure seismic waves: tiny vibrations of the ground surface generated when large amounts of energy are suddenly released underground, such as during earthquakes or nuclear explosions. There are two main kinds of seismic waves. First are body waves, which travel outwards in all directions, including down into the deep Earth, before returning to the surface. Second are surface waves, which travel along Earth’s surface like ripples spreading out on a pond. The difficulty in using seismic waves to monitor underground nuclear tests is distinguishing between explosions and naturally occurring earthquakes. A core goal of monitoring is never to miss an explosion, but there are thousands of sizeable natural quakes around the world every day. As a result, monitoring underground tests is like searching for a potentially non-existent needle in a haystack the size of a planet. Nukes vs quakesMany different methods have been developed to aid this search over the past 60 years. Some of the simplest include analysing the location or depth of the source. If an event occurs far from volcanoes and plate tectonic boundaries, it might be considered more suspicious. Alternatively, if it occurs at a depth greater than say three kilometres, it is unlikely to have been a nuclear test. However, these simple methods are not foolproof. Tests might be carried out in earthquake-prone areas for camouflage, for example, and shallow earthquakes are also possible. A more sophisticated monitoring approach involves calculating the ratio of the amount of the energy transmitted in body waves to the amount carried in surface waves. Earthquakes tend to expend more of their energy in surface waves than explosions do. This method has proven highly effective for identifying underground nuclear tests, but it too is imperfect. It failed to effectively classify the 2017 North Korean nuclear test, which generated substantial surface waves because it was carried out inside a tunnel in a mountain. This outcome underlines the importance of using multiple independent discrimination techniques during monitoring – no single method is likely to prove reliable for all events. An alternative methodIn 2023, my colleagues and I from the Australian National University and Los Alamos National Laboratory in the US got together to re-examine the problem of determining the source of seismic waves. We used a recently developed approach to represent how rocks are displaced at the source of a seismic event, and combined it with a more advanced statistical model to describe different types of event. As a result, we were able to take advantage of fundamental differences between the sources of explosions and earthquakes to develop an improved method of classifying these events. We tested our approach on catalogues of known explosions and earthquakes from the western United States, and found that the method gets it right around 99% of the time. This makes it a useful new tool in efforts to monitor underground nuclear tests. Robust techniques for identification of nuclear tests will continue to be a key component of global monitoring programs. They are critical for ensuring governments are held accountable for the environmental and societal impacts of nuclear weapons testing. Mark Hoggard, DECRA Research Fellow, Australian National University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Why STEM subjects and fashion design go hand in hand (2025-05-09T11:36:00+05:30)

Mark Liu, University of Technology SydneyThe fashion industry evokes images of impossibly beautiful people jet setting around the world in extravagant finery. Like a moth to the flames, it draws many of our most creative young minds. Often, the first instinct of high school students who want to work in creative industries is to drop all their math and science subjects to take up textiles and art. As a fashion and textile designer myself, I would like to explain how this is a bad strategy and how the future of fashion requires science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM skills) more than ever. Beneath the glamorous façade, the fashion industry is undergoing disruptive changes due to rapid advances in technology. We take it for granted that you can use your Iphone to watch a fashion runway show on YouTube, Google the garment to find an online retailer like Net-A-Porter, pay for it using PayPal and then upload a selfie onto Snapchat. None of these services even existed 20 years ago. Materials that were theoretical thirty years ago have become pervasive. So when you buy yoga clothing from Lululemon that are “anti-bacterial” you are actually wearing fabrics that are coated in silver nano-whiskers. Sportswear companies such as Nike and Adidas engage in a technological arms race of materials and technology. The reason why their latest shoes look like something out of science fiction is because the technology is truly cutting edge science. In 2011, Parisian High Fashion forever changed when designer Iris van Herpen was invited as a guest member of La Chambre Syndicale de La Haute Couture. Van Herpen, who makes liberal use of hi tech materials such as magnetic fabric, laser cutters and custom developed thermoplastics which are 3D printed, was embraced by the oldest establishment as “Haute Couture”. Even the supermodel Karlie Kloss advocates the importance of STEM skills for future careers in the tech industry and has a scholarship program Kode with Klossy that teaches young girls computer coding. Fashion is a unique blend of business, science, art and technology. It requires a polymath, a person who can understand all of these skills. The most compelling reasons to learn STEM skills is because technology and rapidly changing business models have made surviving in the business more competitive than ever. If you are running a fashion label you will probably need a business loan or have to justify what you are spending your money on. No matter how brilliant your ideas, the people who control money are only swayed by arguments based on sound financial reasoning. Rates of return, accounting and interest rates are all ideas that can only be well understood using mathematics. Mathematics is mandatory for financial literacy. It introduces ideas such as optimisation, understanding statistics and problem solving and forms a language that allows designers to talk to scientists, engineers and business people. If you are going to study fashion in college, you will need to learn about fabrics, which are material science. No matter how advanced the school syllabus in textiles, by the time you get to college there will be new materials and technology that did not exist before you got there. If you learn chemistry and physics you will understand the underlying scientific principles on a deeper level, making new material science really easy in the future. Learning chemistry in school introduces you to lab protocols, taking measurements and accurately recording experiments. These are the exact skills you will need when working with dyes and pigments in textiles. Using dyes to change the colour of textiles is essentially carbon chemistry. To do this a designer must change the acidity or alkalinity of the fabric - known as the PH level. This allows the “chromophores,” which are the parts of the dye molecule that create colour, to embed into the fabric. The PH scale in chemistry is a logarithmic scale and this is one place where abstract mathematical ideas are actually used in practice. Maths and creativityMathematics can also push the boundaries of creativity in fashion. Designer Dai Fujiwara collaborated with legendary 1982 Fields Medal winning mathematician William Thurston to create radically different garments inspired by geometry and topology. In his 1 32 5 collection Fujiwara collaborated with computer scientist Jun Mitani to create mathematical folding algorithms generating innovative clothing. My own PhD research explores the underlying geometry of how clothing is made and has even been used to teach abstract mathematical concepts through making fashion garments. For a socially minded designer, STEM skills are essential to understanding environmental sustainability. Fashion used to have seasons, but now with fast fashion companies such as Zara and H&M, new clothing is coming into stores in each week. Fast fashion companies are often criticised for being unsustainable and exploiting workers. Sustainability in the fashion industry is an extremely complex issue. It requires an understanding of the underlying science, economic behaviour and business practises of the fashion industry and their environmental impact. The fashion industry is full of “Greenwash,” fake sustainable marketing which has no scientific basis. STEM skills allow you to navigate these complex issues and try to address them for yourself. The future of fashion is uncharted territory, but STEM skills make a budding fashion designer smart and adaptable. Mark Liu, PhD Philosophy, Fashion and Textiles Designer, University of Technology Sydney This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Does the Suzuki method work for kids learning an instrument? Parental involvement is good, but other aspects less so (2025-05-08T13:11:00+05:30)

Giving children an instrumental music education can be expensive. In addition to purchasing an instrument and paying the cost of music lessons, parents invest their time by encouraging practice, attending recitals and driving their child to and from lessons. Parents rightly want value-for-money and confidence that their child’s teacher employs an evidenced-based, proven teaching method. There are numerous approaches to teaching music, each with its own philosophy and history. To a parent looking to make an informed choice about music lessons, the options can be befuddling. But given the research highlights parental involvement as an important component for a successful music-learning experience, developing an understanding of the teaching method is vital. One method that polarises the music education community is Shinichi Suzuki’s (1898-1998) “talent education” (saino kyoiku), commonly known as the Suzuki method. It was first conceived as a system for teaching the violin. The Suzuki method arrived in Australia in the early 1970s and was quickly applied to a variety of instruments. Research highlights a range of positive outcomes for children learning how to play an instrument via the Suzuki method. It also shows Suzuki is not the only method that works. While the degree of parental involvement may mean Suzuki is not right for every family, the caring learning environment it encourages is one worth emulating. What is the Suzuki method?1. Talent is no accident of birth The Japanese word saino has no direct English translation and can, in context, mean “talent” or “ability”. Shinichi Suzuki believed talent is not inherited, and any child could excel musically, given the right learning environment. Today, advocates of the method continue to echo Suzuki’s idea that “the potential of every child is unlimited”, and caring learning environments help children unlock that potential. 2. All Japanese children speak Japanese Suzuki credited the development of saino kyoiku to the realisation the vast majority of young children naturally and easily develop language skills. By examining the experiences that facilitate language development (including listening, imitation, memory and play), Suzuki devised the “mother-tongue” method for early childhood music education. Children can begin their music education from birth through listening, and can start learning an instrument from as young as three years old. In contrast to some Western approaches to music teaching, reading music notation is not prioritised and is delayed until a child’s practical music ability is well established. In the same way a child generally learns to talk before learning to read, students of the Suzuki method start by listening to and imitating music rather than sight reading sheet music. 3. Character first, ability second Taken from the motto of the high school Suzuki attended until 1916, “character first, ability second” is the overriding aim of the Suzuki method. In saino kyoiku, music learning is a means to an end: students are taught an instrument to facilitate them becoming noble human beings. Some students of the Suzuki method have undoubtedly progressed on to a career in music. But creating professional musicians and celebrating child prodigies or virtuosos is not a priority of the method. 4. The destiny of children lies in the hands of their parents The Suzuki method requires a major contribution from a parent and a home environment that wholeheartedly embraces the child’s music-making. A parent needs to participate in formal lessons, record instructions from the teacher and regularly guide and monitor practice at home. The learning process is a three-way relationship between the child, the parent and the teacher. The parent becomes a “home teacher” who helps their child develop new skills, provides positive feedback and guides the content and pacing of practice sessions. The benefit of having a parent-mentor at home is the feature that sets Suzuki apart from other teaching methods. The parent can greatly regulate time spent practising and what they do during practice. Some music teachers have criticised the Suzuki method for teaching children to a high level at an earlier age than usual, for an over-reliance on rote learning, for robotic playing, for a focus on classical music, and for a lack of engagement with music notation and improvisation. What does the research say?

The research into music education supports many aspects of the Suzuki method. For example, one study that sought to compare different modes of parental involvement in music lessons found a clear benefit from parental involvement. This benefit was not limited only to the Suzuki method. The message from this study is: the more interested the parent, the better the learning for the child. Another study compared Suzuki’s approach to teaching rhythm with the BAPNE method (Body Percussion: Biomechanics, Anatomy, Psychology, Neuroscience and Ethnomusicology). The study concluded both methods had merit and should be integrated. A recent thesis from the University of Southern Mississippi compared the Suzuki method with the method of its fiercest critic, the O’Connor method. The O’Connor method is an American system where a set of music books are sold to teachers and students, and training to accredit teachers. These books are tailored to different levels of ability. This method is less focused on parental involvement in teaching and the selection of music is more geared towards American music. The study found the two approaches could both be effective and shared common aspects related to technique, expression and the mechanics of learning the violin. The thesis does claim the O’Connor method embraces a more diverse musical repertoire. But the modern Suzuki organisation says its teachers have more flexibility in incorporating different styles of music. Finally, a study out of South Africa highlights ways the Suzuki method can be adapted for use in different cultural contexts. The authors examined the challenges associated with Suzuki’s requirement for high levels of parental involvement for orphans and children from low-income and single-parent families. These challenges could be overcome by a community approach to music education. In a group learning setting, older and more advanced students mentored younger, less advanced students and provided the encouragement and guidance otherwise provided by a parent. Some aspects of the Suzuki method remain steeped in controversy. There is no reliable evidence to support the idea that musical training improves character and a sizeable body of research contradicts the notion that genetics has no role in musical aptitude. Timothy McKenry, Professor of Music, Australian Catholic University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

From the Moscow stage to Monroe and De Niro: how the Method defined 20th-century acting (2025-03-31T13:16:00+05:30)

|

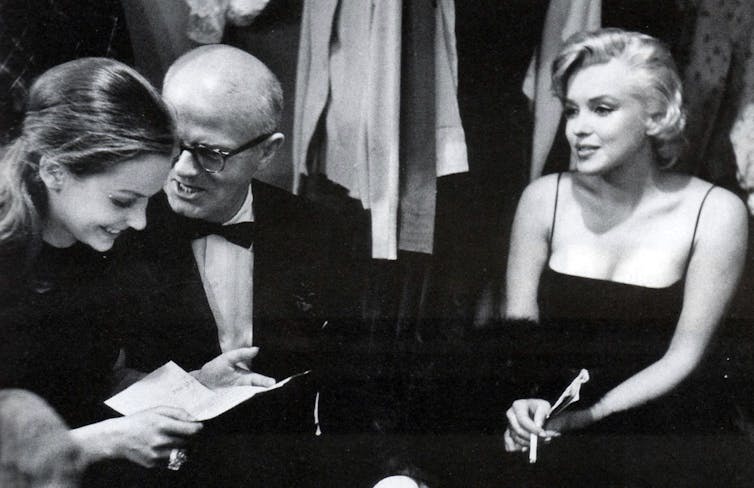

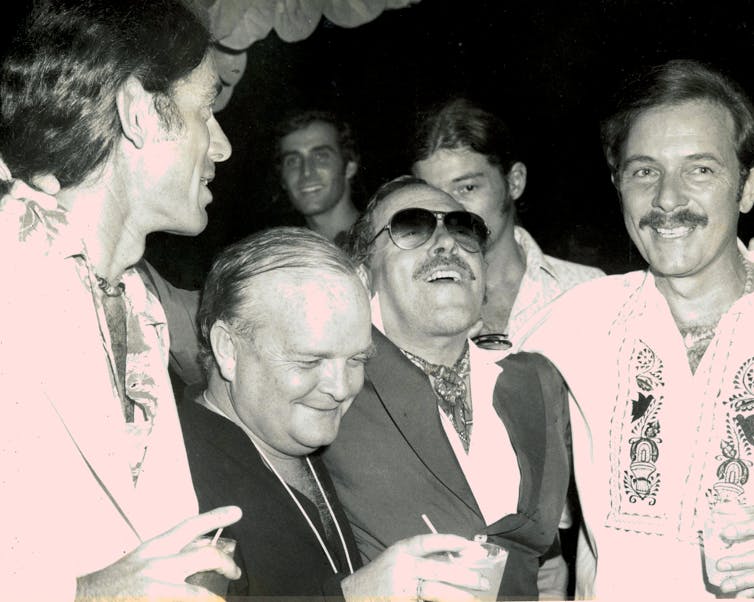

When an actor is criticised for peculiarly excessive preparation for a role, or an inability to break character off-camera, an ill-defined notion of “Method” acting (note the capital “M”) is rarely far away. Review: The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act by Isaac Butler (Bloomsbury). Living rough on the streets to prepare for a role. Abusing fellow performers to provoke an “authentic” response. Or never breaking from character throughout an entire shoot – like Daniel Day-Lewis, who supposedly insisted on being addressed as “Mr President” throughout the three-month filming of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. But while it’s easy to ridicule or parody, the Method – which casts a long shadow over European and (in particular) American acting – is complex and varied. What is Method acting?As detailed in Isaac Butler’s The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act, the Method was developed in Russia in the latter part of the 19th century.  Its creators, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislawski, transformed Russian theatre with their new approach to acting, writing and theatre production. Their system encouraged more subjective, interior approaches to performance, and more realistic, naturalistic approaches to staging. Acting had been largely externalised and action-centred, often understood in terms of preconceived gestures. The Method helped transform it into a dynamic process that unlocked deep recesses of personal experience and “emotion memory”, which could then be funnelled into a performance. It is hard to imagine modern acting without this development. Collateral damage to shooting starsThe Method is strongly linked to the new realism that emerges in New York theatre in the 1930s and 1940s, and Hollywood cinema in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s also connected to the performance styles of many of the key actors and stars of mid-century American theatre and cinema: Marlon Brando, Kim Stanley, Montgomery Clift, Anne Bancroft, Rod Steiger, Paul Newman, and many others. Its excesses and dangers are deployed as damning evidence to help explain the tragic fate of figures like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe. Shooting stars caught within the orbit of abusive Method teachers, they seemed to suffer the collateral damage of drawing on their traumatic past too deeply. The Method is often brought into debates about the distinction between performing and being, acting and reacting. But such dichotomies are unhelpful in understanding the complex interior, exterior and collaborative processes at play in any great performance. This is particularly true for film acting, a mode of performance that requires actors to register minute changes of expression, small actions and gestures – all of which are then blown up in microscopic detail.  Anne Bancroft is a key mid-century actor whose performance style is linked to the Method. She’s pictured (right) with Dustin Hoffman, another famous Method actor, in The Graduate. IMDB Anne Bancroft is a key mid-century actor whose performance style is linked to the Method. She’s pictured (right) with Dustin Hoffman, another famous Method actor, in The Graduate. IMDBAs James Harvey has claimed, the art of acting for the camera in the 20th century is largely a matter, for the spectator, of “watching them be”. In some ways, the Method, which at its base foregrounds individual agency and psychology, is brilliantly suited to self-centred notions of both society and art. And to the curious alchemy that fuses actor, celebrity and character in star-centred theatre and cinema. It is unsurprising that this often mannered style reached its peak of fame in the 1950s, an era of rising individualism. It rocketed to ascendancy alongside Abstract Expressionism in American painting, stream of consciousness in various forms of writing (such as the work of the Beats), and in the improvisational modes of jazz favoured by artists like Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman. Revolution, individualism and FreudIsaac Butler’s book is a fascinatingly detailed, brilliantly readable and often compelling account of the hundred-year journey of the Method from pre-revolutionary Russia to the stages of New York – and the rise of New Hollywood and actors like Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Ellen Burstyn.  Method actor Al Pacino and Lee Strasberg, famous Method acting teacher (and actor), in The Godfather II, as Michael Coreleone and Hyman Roth. IMDB Method actor Al Pacino and Lee Strasberg, famous Method acting teacher (and actor), in The Godfather II, as Michael Coreleone and Hyman Roth. IMDBIt is not shy in exploring the complexities of this journey and the many offshoots and variations produced along the way. Butler examines the social, cultural and political implications of the evolving and splintering Method system, and how it responded to various forces. These include: proletarian demands, the Russian revolution, the rise of leftist politics in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, Freudian psychology, the increased individualism of post-war America, and the anti-communist blacklist. And, of course, there was the Method’s ultimate canonisation and popular recognition in plays and films like A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, and Marty. Butler also meticulously introduces and describes the first-tier actors and directors of the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s who proclaimed (and in some cases denied) the Method’s direct influence and legacy. For a significant period in the 1960s and 1970s, with the increasing celebrity of prominent acting teachers of the Method like Lee Strasberg (of the Actors Studio) and Stella Adler, the Method’s various offshoots could claim true cultural dominance. The influence and fiery disagreements of these teachers are a focus of Butler’s book. Butler details Marilyn Monroe’s increasingly close and personal relationship with Strasberg (and his relationship with second wife Paula, Monroe’s acting coach) and the influential patronage of actors like James Dean, Montgomery Clift and Rod Steiger. He also describes truly terrifying classes and feedback sessions conducted by Strasberg at the Actors Studio.  Method acting coach Lee Strasberg (centre) with actor daughter Susan Strasberg (left) and famous student Marilyn Monroe (right). Laura Loveday/Flickr, CC BY Method acting coach Lee Strasberg (centre) with actor daughter Susan Strasberg (left) and famous student Marilyn Monroe (right). Laura Loveday/Flickr, CC BYIn contrast, Adler insisted on an approach to acting that stuck more closely to Stanislawski’s original concept of “emotion memory”, and recommended extensive processes of research and preparation in the creation of any performance. Among her most significant students were Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Elaine Stritch and Warren Beatty. A particular strength of Butler’s cultural history is how he carefully plots this rise, while granting equal space to each stage of the journey. His book is, nevertheless, a little too focused on the impact of the ideas of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislavski on the stages and screens of Russia and then the United States. There is little sense of the impact of these ideas elsewhere in Europe, and British acting is mainly used as a counterweight, put forward as a haven for a more exterior form of acting, epitomised by the work of Laurence Olivier (who famously scorned Method acting). Butler also provides accounts of writers important to the Method. Anton Chekhov, central to the initial work of the seminal Moscow Open Art Theatre, is a key source throughout. And he charts the contributions of Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin and Paddy Chayefsky, who were equally integral to various stages of the Method’s development, dissemination and devolution.  Tennessee Williams was one of the writers integral to various stages of the Method’s development. He’d pictured here (third from left), with Truman Capote (second from left). From the Key West Art and Historical Society. Florida Keys Public Library/Flickr, CC BY Tennessee Williams was one of the writers integral to various stages of the Method’s development. He’d pictured here (third from left), with Truman Capote (second from left). From the Key West Art and Historical Society. Florida Keys Public Library/Flickr, CC BYThe book gives space to the competing approaches of writers and directors like Bertolt Brecht and Vsevolod Meyerhold, along with the more varied approaches of actors like Meryl Streep. Its compelling chronological narrative ends up focusing, however, on a judicious selection of key figures within the US and Russia. As Butler documents, the outcomes of this change – though he is also careful to note the seeds of this style even earlier and elsewhere – could be truly astounding or monumentally disastrous. Triumphs, failures and major playersAmong the pleasures of Butler’s book is how it documents these triumphs and failures – sometimes within the performance of the same play by a single company, as in the case of the Actors Studio’s staging of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. He also provides evocative portraits of many key figures like Elia Kazan, Maria Ouspenskaya, Howard Clurman, Richard Boleslavsky and John Garfield. He focuses on people who were particularly important in managing entities such as the American Laboratory Theatre, the Actors Studio, the Group Theatre and the Moscow Art Theatre, directing breakthrough films and plays (the duplicitous Kazan emerges as a titan in this regard), writing accounts of how the “system” worked, or introducing new styles of acting.  Konstantin Stanislawski. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY Konstantin Stanislawski. Wikimedia Commons, CC BYAs in many books of this kind, such a focus and approach is also a limitation. This is a cultural history less concerned with the nuts and bolts of theatre and film production – though it is often incisive in this department and is plainly written by someone with a deep knowledge of these processes – than the collaborations and conflicts between figures adapting and transforming Stanislavski’s initial “system”. This, of course, also makes this very well-written and carefully organised book a true pleasure to read. Butler provides a convincing account of the Method’s importance in the history of ideas. He doesn’t shy away from arguing for the decreased currency of many of its techniques and lessons, but make claims for its ongoing influence alongside a range of other approaches and methods. He provides a complex account of The Method’s various forms and variations across almost 150 years. He also provides important cultural and social context for helping understand why a shift to a more “realist” or personal, self-centred form of acting was both hard fought for and inevitable. Even a simple thing like the improved lighting in theatres from the late 19th century had a profound impact on what was possible in terms of more interior and subtle forms of staging and performance. This was, of course, amplified in the rise of sound cinema in the late 1920s and its more tempered forms of screen acting that led to the minimalist styles of stars like Gary Cooper, Clint Eastwood and Juliette Binoche. Popular accounts of the Method’s legacy tend to steer towards trivial excesses, like Jared Leto allegedly sending his co-stars various “gifts” like used condoms in preparation for his role as the Joker in Suicide Squad. (Which, for the record, Leto now denies.) But Butler’s book makes convincing claims for why we should continue to take this approach and its legacy seriously. In so doing, it answers its pointed epigraph from Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: “We’re actors. We’re the opposite of people.” If this magisterial book does little else, it certainly convinces the reader that nothing could be further from the truth. Adrian Danks, Associate professor in Cinema and Media Studies, RMIT University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

The butterfly effect: this obscure mathematical concept has become an everyday idea, but do we have it all wrong? (2025-02-20T13:41:00+05:30)

In 1972, the US meteorologist Edward Lorenz asked a now-famous question:

Over the next 50 years, the so-called “butterfly effect” captivated the public imagination. It has appeared in movies, books, motivational and inspirational speeches, and even casual conversation. The image of the tiny flapping butterfly has come to stand for the outsized impact of small actions, or even the inherent unpredictability of life itself. But what was Lorenz – who is now remembered as the founder of the branch of mathematics called chaos theory – really getting at? A simulation goes wrongOur story begins in the 1960s, when Lorenz was trying to use early computers to predict the weather. He had built a basic weather simulation that used a simplified model, designed to calculate future weather patterns. One day, while re-running a simulation, Lorenz decided to save time by restarting the calculations from partway through. He manually inputted the numbers from halfway through a previous printout. But instead of inputting, let’s say, 0.506127, he entered 0.506 as the starting point of the calculations. He thought the small difference would be insignificant. He was wrong. As he later told the story:

There was no randomness in Lorenz’s equations. The different outcome was caused by the tiny change in the input numbers. Lorenz realised his weather model – and by extension, the real atmosphere – was extremely sensitive to initial conditions. Even the smallest difference at the start – even something as small as the flap of a butterfly’s wings – could amplify over time and make accurate long-term predictions impossible. Lorenz initially used “the flap of a seagull’s wings” to describe his findings, but switched to “butterfly” after noticing a remarkable feature of the solutions to his equations.

In his weather model, when he plotted the solutions, they formed a swirling, three-dimensional shape that never repeated itself. This shape — called the Lorenz attractor — looked strikingly like a butterfly with two looping wings. Welcome to chaosLorenz’s efforts to understand weather led him to develop chaos theory, which deals with systems that follow fixed rules but behave in ways that seem unpredictable. These systems are deterministic, which means the outcome is entirely governed by initial conditions. If you know the starting point and the rules of the system, you should be able to predict the future outcome. There is no randomness involved. For example, a pendulum swinging back and forth is deterministic — it operates based on the laws of physics. Systems governed by the laws of nature, where human actions don’t play a central role, are often deterministic. In contrast, systems involving humans, such as financial markets, are not typically considered deterministic due to the unpredictable nature of human behaviour. A chaotic system is a system that is deterministic but nevertheless behaves unpredictably. The unpredictability happens because chaotic systems are extremely sensitive to initial conditions. Even the tiniest differences at the start can grow over time and lead to wildly different outcomes. Chaos is not the same as randomness. In a random system, outcomes have no definitive underlying order. In a chaotic system, however, there is order, but it’s so complex it appears disordered. A misunderstood memeLike many scientific ideas in popular culture, the butterfly effect has often been misunderstood and oversimplified. One common misconception is that the butterfly effect implies every small action leads to massive consequences. In reality, not all systems are chaotic, and for systems that aren’t, small changes usually result in small effects. Another is that the butterfly effect carries a sense of inevitability, as though every butterfly in the Amazon is triggering tornadoes in Texas with each flap of its wings. This is not at all correct. It’s simply a metaphor pointing out that small changes in chaotic systems can amplify over time, making long-term outcomes impossible to predict with precision. Taming butterfliesSystems that are very sensitive to initial conditions are very hard to predict. Weather systems are still tricky, for example. Forecasts have improved a lot since Lorenz’s early efforts, but they are still only reliable for a week or so. After that, small errors or imprecisions in the starting data grow larger and larger, eventually making the forecast inaccurate. To deal with the butterfly effect, meteorologists use a method called ensemble forecasting. They run many simulations, each starting with slightly different initial conditions. By comparing the results, they can estimate the range of possible outcomes and their likelihoods. For example, if most simulations predict rain but a few predict sunshine, forecasters can report a high probability of rain. However, even this approach works only up to a point. As time goes on, the predictions from the models diverge rapidly. Eventually, the differences between the simulations become so large that even their average no longer provides useful information about what will happen on a given day at a given location. A butterfly effect for the butterfly effect?The journey of the butterfly effect from a rigorous scientific concept to a widely popular metaphor highlights how ideas can evolve as they move beyond their academic roots. While this has helped bring attention to a complex scientific concept, it has also led to oversimplifications and misconceptions about what it really means. Attaching a metaphor to a scientific phenomenon and releasing it into popular culture can lead to its gradual distortion. Any tiny inaccuracies or imprecision in the initial description can be amplified over time, until the final outcome is a long way from reality. Sound familiar? Milad Haghani, Associate Professor & Principal Fellow in Urban Risk & Resilience, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Does the Suzuki method work for kids learning an instrument? Parental involvement is good, but other aspects less (2025-02-11T12:00:00+05:30)

Giving children an instrumental music education can be expensive. In addition to purchasing an instrument and paying the cost of music lessons, parents invest their time by encouraging practice, attending recitals and driving their child to and from lessons. Parents rightly want value-for-money and confidence that their child’s teacher employs an evidenced-based, proven teaching method. There are numerous approaches to teaching music, each with its own philosophy and history. To a parent looking to make an informed choice about music lessons, the options can be befuddling. But given the research highlights parental involvement as an important component for a successful music-learning experience, developing an understanding of the teaching method is vital. One method that polarises the music education community is Shinichi Suzuki’s (1898-1998) “talent education” (saino kyoiku), commonly known as the Suzuki method. It was first conceived as a system for teaching the violin. The Suzuki method arrived in Australia in the early 1970s and was quickly applied to a variety of instruments. Research highlights a range of positive outcomes for children learning how to play an instrument via the Suzuki method. It also shows Suzuki is not the only method that works. While the degree of parental involvement may mean Suzuki is not right for every family, the caring learning environment it encourages is one worth emulating. What is the Suzuki method?1. Talent is no accident of birth The Japanese word saino has no direct English translation and can, in context, mean “talent” or “ability”. Shinichi Suzuki believed talent is not inherited, and any child could excel musically, given the right learning environment. Today, advocates of the method continue to echo Suzuki’s idea that “the potential of every child is unlimited”, and caring learning environments help children unlock that potential. 2. All Japanese children speak Japanese Suzuki credited the development of saino kyoiku to the realisation the vast majority of young children naturally and easily develop language skills. By examining the experiences that facilitate language development (including listening, imitation, memory and play), Suzuki devised the “mother-tongue” method for early childhood music education. Children can begin their music education from birth through listening, and can start learning an instrument from as young as three years old. In contrast to some Western approaches to music teaching, reading music notation is not prioritised and is delayed until a child’s practical music ability is well established. In the same way a child generally learns to talk before learning to read, students of the Suzuki method start by listening to and imitating music rather than sight reading sheet music. 3. Character first, ability second Taken from the motto of the high school Suzuki attended until 1916, “character first, ability second” is the overriding aim of the Suzuki method. In saino kyoiku, music learning is a means to an end: students are taught an instrument to facilitate them becoming noble human beings. Some students of the Suzuki method have undoubtedly progressed on to a career in music. But creating professional musicians and celebrating child prodigies or virtuosos is not a priority of the method. 4. The destiny of children lies in the hands of their parents The Suzuki method requires a major contribution from a parent and a home environment that wholeheartedly embraces the child’s music-making. A parent needs to participate in formal lessons, record instructions from the teacher and regularly guide and monitor practice at home. The learning process is a three-way relationship between the child, the parent and the teacher. The parent becomes a “home teacher” who helps their child develop new skills, provides positive feedback and guides the content and pacing of practice sessions. The benefit of having a parent-mentor at home is the feature that sets Suzuki apart from other teaching methods. The parent can greatly regulate time spent practising and what they do during practice. Some music teachers have criticised the Suzuki method for teaching children to a high level at an earlier age than usual, for an over-reliance on rote learning, for robotic playing, for a focus on classical music, and for a lack of engagement with music notation and improvisation. What does the research say?

The research into music education supports many aspects of the Suzuki method. For example, one study that sought to compare different modes of parental involvement in music lessons found a clear benefit from parental involvement. This benefit was not limited only to the Suzuki method. The message from this study is: the more interested the parent, the better the learning for the child. Another study compared Suzuki’s approach to teaching rhythm with the BAPNE method (Body Percussion: Biomechanics, Anatomy, Psychology, Neuroscience and Ethnomusicology). The study concluded both methods had merit and should be integrated. A recent thesis from the University of Southern Mississippi compared the Suzuki method with the method of its fiercest critic, the O’Connor method. The O’Connor method is an American system where a set of music books are sold to teachers and students, and training to accredit teachers. These books are tailored to different levels of ability. This method is less focused on parental involvement in teaching and the selection of music is more geared towards American music. The study found the two approaches could both be effective and shared common aspects related to technique, expression and the mechanics of learning the violin. The thesis does claim the O’Connor method embraces a more diverse musical repertoire. But the modern Suzuki organisation says its teachers have more flexibility in incorporating different styles of music. Finally, a study out of South Africa highlights ways the Suzuki method can be adapted for use in different cultural contexts. The authors examined the challenges associated with Suzuki’s requirement for high levels of parental involvement for orphans and children from low-income and single-parent families. These challenges could be overcome by a community approach to music education. In a group learning setting, older and more advanced students mentored younger, less advanced students and provided the encouragement and guidance otherwise provided by a parent. Some aspects of the Suzuki method remain steeped in controversy. There is no reliable evidence to support the idea that musical training improves character and a sizeable body of research contradicts the notion that genetics has no role in musical aptitude. Timothy McKenry, Professor of Music, Australian Catholic University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |