Vlad Deep/ Unsplash

Anabela Malpique, Edith Cowan University and Deborah Pino Pasternak, University of Canberra

Writing using computers is a vital life skill. We are constantly texting, posting, blogging and emailing. This is a huge change for schools when it comes to teaching writing. For students, learning how to write on a computer is crucial. National literacy tests are now administered online in many countries, including Australia’s NAPLAN. The rise of AI tools such as ChatGPT still require students to become expert writers so they can prompt the technology and judge the quality of its products. However, despite its importance, our new research shows typing and word processing skills are often not explicitly taught in primary schools. Why is it so important to learn how to write on a computer?Research suggests teaching typing and word processing skills should start in primary school, much like writing with pen and paper. There is no evidence-based recommendation for specific ages to start, but it should also be taught as schools introduce students to computers. This is crucial to avoid incorrect key locations and hand and finger positions, which are difficult to correct later. This is not necessarily a skill children will pick up naturally. Research shows children who are explicitly taught typing and word processing together write longer and better computer-based texts than those who have not been taught. Our studyDespite computers being introduced to classrooms in the 1990s, there is little information about how typing and word processing are being taught in Australian schools. In the first national study of its kind, we surveyed 340 Australian primary teachers from government, Catholic and private sectors across all states and territories about computer-based writing. There’s no recommended amount for teaching computer-based writing. However, recommendations for teaching writing overall are to spend at least one hour per day on writing skills. Similar to previous overseas studies, teachers in our study spent significantly more time teaching paper-based writing than computer-based writing skills. Overall, students spent an average of 143 minutes per week writing texts using paper and pen or pencil. They spent an average of 57 minutes per week writing using a digital device. The explicit teaching of keyboard use received an average of nine minutes per week, compared to 31 minutes for handwriting. Teaching computer-based writing skills was less frequent among teachers of years 1 to 3, when compared with years 4 to 6. What are the barriers?We also asked teachers whether they thought it was important to teach computer-based writing skills. More than 98% agreed it was important to teach keyboarding and word-processing skills. About 40% of respondents said specialised lab assistants should be available to help teach students in the junior primary years. But teachers reported there were no official programs to teach typing and computer-based writing in their schools. As one told us:

Teachers also reported a lack of access to keyboards to teach computer-based writing skills. Only 17% said their students had access to devices with external keyboards (keyboards separate to the screen) in the classroom. When asked about their confidence to teach computer-based writing skills, most teachers (74%) said they had not been adequately prepared during their teacher education. Most (84%) reported they had little confidence teaching their students how to create texts using digital devices. As one teacher said:

What now?Our research suggests we need three key changes to better support young Australian students to learn how to type and write on a keyboard.

We know writing supports thinking and learning. It is also one of the key skills students learn at school. Primary students must be supported to develop computer-based writing skills so they can be skilful writers in our increasingly digital world. Anabela Malpique, Senior Lecturer in Literacy, Edith Cowan University and Deborah Pino Pasternak, Professor in Early Childhood Education and Community, University of Canberra This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Australian students spend more time learning to write on paper than computers – does this need to change? (2025-12-01T11:41:00+05:30)

Expert panel: what makes a good teacher (2025-10-16T13:42:00+05:30)

David Zyngier, Monash University; Andrew J. Martin, UNSW Sydney; John Loughran, Monash University, and Robyn Ewing, University of SydneyAmid debates about teacher quality and training, and with the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group soon to report on teacher education, we asked a panel of experts just what makes a good teacher. David Zyngier, Monash University From my research on student engagement, a good teacher practises CORE pedagogy where the teaching Connects with the children’s background, students have Ownership of what is being taught, Responds to the students’ needs and Empowers students to see that education can make a difference to their lives. When this is combined with Pedagogical Reciprocity - that is teachers and students learning with and from each other - teaching and learning is at its best for all children, but especially those from disadvantaged and minority communities.

John Loughran, Monash University Teach instead of tell The stereotype of teaching is of someone standing up in front of a class talking. Unfortunately, because of that image, teaching is too often misinterpreted as being about the simple delivery of information. So when politicians feel the urge to fix education, they typically focus on the information delivered to students. A typical refrain is that our education rankings would be better if we fixed the curriculum and delivered the right information. One way of teaching does not sit comfortably with theories of learning such as multiple intelligences and all that we know about the range of learning styles in every classroom. It is clear that educational practices must go beyond simplistic views of telling as teaching and listening as learning if we are to genuinely pursue quality in schooling. So how can a teacher manage the competing demands of 25 or so different student learners in a classroom? When doctors work to diagnose a patient’s illness, they begin to develop an overview of the major symptoms, sort through information and ideas to analyse the situation and begin to consider multiple possibilities and likely responses to the situation simultaneously. Why would we imagine that teachers are any different? Maybe it is because, when watching teaching, we do not see the thinking that teachers are engaged in as they diagnose and respond to their learners’ needs. If telling as teaching dominates, then there is only one response. Sadly, those learners who find it hard to grasp what they are told and to retain it will struggle to succeed. However, thoughtful, well-informed, flexible and adaptive professional teachers develop multiple approaches to supporting their students’ learning. When teachers are confronted by students’ learning issues, they are offered opportunities to broaden their knowledge base for diagnosis. Importantly, they also begin to consider alternative ways to address the situation; that is, they find an appropriate approach for the given situation. If quality teaching is understood as continually building knowledge, skills and ability in the complex work of diagnosing and appropriately responding to diverse learning needs, then expert teachers are those that are able to put that learning into practice in different subjects, with multiple learners, in the same space and at the same time. Andrew Martin, University of New South Wales Teacher-Student Relationships My main area of research is student motivation and engagement. Motivation is students’ inclination, interest, energy and enthusiasm to learn and achieve. Engagement refers to the behaviours (such as persistence and effort) that emanate from this motivation. Increasingly, our research is demonstrating the substantial role that teacher-student relationships play in facilitating students’ motivation and engagement. Put simply, the extent to which students are receptive to anything a teacher may say or do to motivate and engage them will rely heavily on the relationship the teacher has developed with the students. In our research program we have found that good teacher-student relationships are significantly associated with students’ self-confidence, valuing of school, positive goals, learning focus, planning, educational aspirations, class participation and persistence. We have also found good teacher-student relationships are associated with lower anxiety, fear of failure, and disengagement. Indeed, our research has suggested that the role of teacher-student relationships is independent of the role that parents and caregivers play in impacting students’ academic motivation and engagement. Teachers are not a seven-hour Band-Aid that is undone once a child gets home from school: the teacher’s influence is unique and ongoing. Now here’s the catch: teachers can’t set aside 4-6 weeks at the start of every academic year getting to know every child in the classroom. The curriculum and associated accountabilities march on and teachers cannot afford to fall behind. Thus, the challenge is for teachers to embed relationships into the everyday course of their pedagogy – from day one. This is no easy task. The other challenge is that teacher-student relationships are multi-faceted. In fact, there are three key facets to teacher-student relationships:

We refer to this type of relational instruction as “connective instruction”. In fact, we liken a great lesson to a great musical composition: it takes a great singer (WHO), a great song (WHAT) and great singing (HOW). When a student connects with the teacher and teaching on all three dimensions, there is truly a great teacher-student relationship happening in the learning context. That is when students are most likely to be motivated and engaged. Robyn Ewing, University of Sydney In my view “good” teaching is not about a set of techniques that can be applied like recipes. As world-renowned author and educator Parker Palmer says, “we teach who we are” – our own identity is central to our ability to connect with our students and to help them learn a particular concept, idea, discipline or subject. We have to be passionate learners ourselves and understand that teaching is an art that we can always develop and refine. Good teachers need to be able to develop strong relationships with their students as individuals. This is a tall order in a class of 20 or 30 students, but it is only with an understanding of each child’s interests, needs, understandings, abilities and learning styles that teachers can best draw on their various teaching and learning strategies to ensure each learner is motivated and engaged in class. Good teachers are mentors as well as co-learners with their students. They have to have the capacity to inspire students to learn and stretch their abilities. At the same time good teachers are keen to learn from their students. Their own love for learning ensures they constantly reflect on their teaching. They make sure their own learning continues throughout their career. Good teachers understand that a child’s social and emotional well-being is critical for them to learn. They also know that arts experiences and processes are central to who we are as human beings and can encourage creative learning. Good teachers embed arts-rich learning opportunities across the curriculum to enhance their learners’ opportunities to develop their imaginations and creative potential. Research demonstrates that such learning experiences will enhance children’s academic, social and spiritual achievements. David Zyngier, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Education, Monash University; Andrew J. Martin, Professor of Educational Psychology, UNSW Sydney; John Loughran, Dean, Faculty of Education, Monash University, and Robyn Ewing, Professor of Teacher Education and the Arts, University of Sydney This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Blending heritage with modern farming (2025-08-01T12:03:00+05:30)

Participants engage in hands-on bamboo craft training during the SSU Skill Development Workshop at Sungratsu. SSU workshop equips students with traditional craft and modern organic farming techniques MOKOKCHUNG, JUNE 26 (MExN): The Sungratsu Students Union (SSU) organised a two-day skill development workshop from June 24 to 25 under the theme “Self-Reliance,” aimed at empowering the Arju Centre, Sungratsu. The workshop sought to blend traditional cultural knowledge with modern organic farming techniques, equipping students with practical skills for sustainable living and income generation. On the first day, held at Senden Salang, Sungratsu, students received hands-on training in bamboo craftsmanship, learning to make items such as baskets, mats, indigenous plates, and machete handles. Sessions also included value addition techniques like pickle-making from leftover products. Alongside the practical training, theory classes delved into folklore, tradition, and the cultural heritage nurtured through the Arju (boys' dormitory) and Tsuki (girls' dormitory) systems.  Master trainers emphasised that bamboo crafts are not just functional tools but represent the stories, customs, and identity of the community. SSU President Tekameren Aier said the crafts reflect the village’s rich heritage and could serve as viable livelihood options when preserved and passed on. Senior student leader Lanulemba Longchar said the broader objective was to instil cultural pride and self-reliance. “This isn’t just about skills,” he said. “It’s about ensuring our traditions live on and helping students realise they can create value from what’s already around them.”  On the second day, participants visited Yimchalu, a tourist farm village, where they observed organic green tea processing and engaged in agricultural and allied activities. These sessions were led by experts from Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK), Yimsemyong, Mokokchung, and focused on the practical aspects of organic farming, kitchen gardening, and local raw material utilisation for marketable products. Lanulemba underscored the need for resource awareness, stating, “The goal is to raise individuals who are not liabilities but contributors to society.” Day one trainers included K Zulu Lemtur, Nokenwapang Ozukum, Imolila, Mejongsangla, Alisoa Aier, Shilutemsu Walling, Rediwapang, De Temjensangla Pongener, Chubayondang Walling, and Takawati Walling.Day two resource persons were C Wati Walling, Village Council Chairman of Yimchalu, and Dr Sarenti from KVK Yimsemyong, along with his team. Blending heritage with modern farming | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

Scientists Use Stones to Build Canoe Like Their Ancestors and Sailed it 140 Miles Across Dangerous Waters (2025-07-15T11:21:00+05:30)

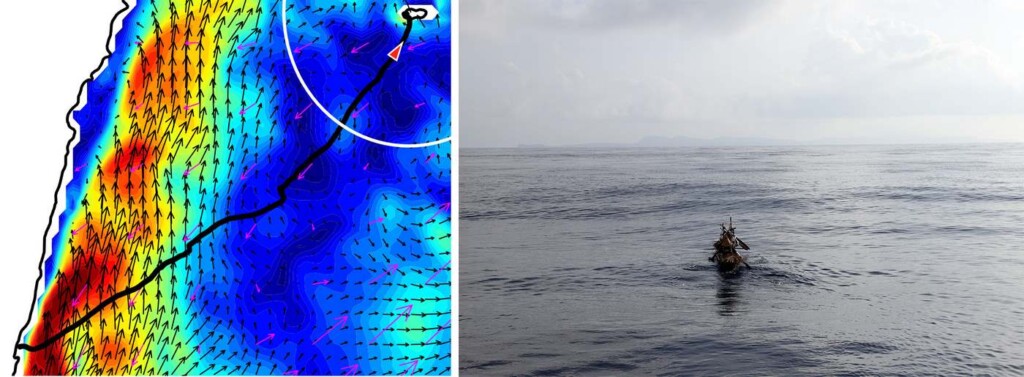

The team in action on their 30,000 year old canoe – credit University of Tokyo A team of scientists who could only be described as ‘intrepid’ sailed several hundred miles across the East China Sea in an ancient replica canoe. The peopling of the Pacific islands has long been one of the great mysteries of anthropology, and the Japanese researchers wanted to do their own small part in unraveling it by answering a question: how did Paleolithic people get from Taiwan to Japan’s southernmost island of Yonaguni.  A map of the team’s canoe voyage from Taiwan to the Japanese island of Yonaguni credit – University of Tokyo While the distance of 140 miles isn’t mighty when compared to some of the voyages the Polynesians are known to have made, it crosses an area plied by one of the strongest currents in the world called the Kuroshio. In two new papers, researchers from Japan and Taiwan led by Professor Yousuke Kaifu from the University of Tokyo simulated methods ancient peoples would have needed to accomplish this journey, and they used period-accurate tools to create the canoes to make the journey themselves. Of the two newly published papers, one used numerical simulations. The simulation showed that a boat made using tools of the time, and the right know-how, could have navigated the Kuroshio. The other paper detailed the construction and testing of a real boat which the team successfully used to paddle between islands. “We initiated this project with simple questions: How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? How difficult was their journey? And what tools and strategies did they use?” said Kaifu in a press release from the University of Tokyo. “Archaeological evidence such as remains and artifacts can’t paint a full picture as the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away. So, we turned to the idea of experimental archaeology, in a similar vein to the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947 by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl.” The Kon-Tiki expedition was a fantastic exercise in getting out of the library, as Indiana Jones said. Seeking to confirm his theory that prehistoric humans may have sailed across the Pacific, Heyerdahl recruited an international team of sailors, craftsmen, explorers, and scientists, and built a raft of primitive materials called Kon-Tiki, which they used to sail from South America to the Tuamotus, across more than 3,000 miles of open ocean. In 2019, the Taiwanese-Japanese team constructed a 23-foot-long dugout canoe called Sugime, built from a single Japanese cedar trunk, using replicas of 30,000-year-old stone tools. They paddled it 140 miles from eastern Taiwan to Yonaguni Island in the Ryukyu group, which includes Okinawa, navigating only by the sun, stars, swells and their instincts. They paddled for over 45 hours across the open sea, mostly without any visibility of the island they were targeting. Several years later, the team is still unpicking some of the data they created during the experiment, and using what they find to inform or test models about various aspects of sea crossings in that region so long ago.  A single Japanese ceder tree was used to make the canoe – credit University of Tokyo Kaifu monologued about the team’s findings and revelations, a full 6 years after their expedition. “A dugout canoe was our last candidate among the possible Paleolithic seagoing crafts for the region. We first hypothesized that Paleolithic people used rafts, but after a series of experiments, we learned that these rafts are too slow to cross the Kuroshio and are not durable enough.” “We now know that these canoes are fast and durable enough to make the crossing, but that’s only half the story. Those male and female pioneers must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown.” “Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance. For example, the ancient Polynesian people had no maps, but they could travel almost the entire Pacific. There are a variety of signs on the ocean to know the right direction, such as visible land masses, heavenly bodies, swells, and winds. We learned parts of such techniques ourselves along the way.”  GPS tracking and modeling of ocean currents toward the end of the experimental voyage – credit, Kaifu et al. CC ND-BY One interesting note was that the team felt any return journey would have been much more difficult, if not altogether impossible, in part because the Kurushio current is varied, and facing it in reverse would have been even tougher. According to the teams’ data, on a vessel launched off the eastern coast of Taiwan as theirs’ was, the Kuroshio runs hard northward along the coastline. Throughout their paddling, they had to compensate for a headwind, and the current seeking to pull them back north. Their GPS trail shows that they missed several zones of deep water where the Kuroshio changes and begins to tug eastward, as well as an area where the current forms something like an ocean gyrate that could have sent them in multiple directions. They navigated the hazardous current brilliantly, but to do so in reverse would have been extremely difficult. They would have been moving against the current in all periods, and from the start it would be trying to pull them out to open ocean.“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were. One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers.” Scientists Use Stones to Build Canoe Like Their Ancestors and Sailed it 140 Miles Across Dangerous Waters |

IS IT CANCER OR THE THOUGHT OF CANCER THAT DESTROYS US? (2025-07-08T13:52:00+05:30)

Figure 1.0: Rawpixel. PSD Aesthetic Flower Instagram Story. Rawpixel, https://www.rawpixel.com/image/7024779/psd-aesthetic-flower-instagram-story. Accessed 10 June 2025. Throughout our lives, some experiences carry more weight than others. People say it takes 3 seconds for everything around you to change – for you to start viewing everything differently. Those 3 seconds of my life were hearing that my beloved grandmother had been diagnosed with cancer. A moment that arrived unexpectedly yet left a scar that only time could heal. The word cancer itself held more power over us than any reports. Throughout our lives, the only thing associated with cancer was pain and suffering. Our family didn’t fear cancer because we understood it fully but because of how it was perceived in society. Cancer, over the past 200 million years, has meant a frightening and puzzling set of diseases causing detrimental changes within all living beings. The agents of destruction in cancer, unlike other diseases and sicknesses, are our own human cells that are transformed into oncogenes – also called cancer-causing genes. These so-called “transformations” are carried out by cancer-causing agents. This includes biological, physical and chemical components like viruses, UV radiation exposure, etc. Over the years, we have come to know of various forms of cancers that are classified on the basis of their origin. For example, carcinoma is a type of cancer that arises in epithelial cells; sarcoma originates in connective or supportive tissues; leukaemia is caused in blood-forming tissues (bone marrow); and the list goes on. Despite rapid innovations in the fields of technology and scientific research, our ability to understand various forms of cancer and their origins continues to develop. Although a definitive cure remains a mystery. As new types of cancers continue to emerge and existing ones take more complex forms, the challenge of finding the ideal combat strategy persists. In the past few years, there have been rapid enhancements in developing early detection machines and targeted therapies. Yet cancer, to this date, remains one of the most formidable health issues worldwide. The form of cancer that my grandmother was diagnosed with is called glioblastoma. This form of cancer is one of the most aggressive and malignant brain tumours originating in the glial cells. It’s known for its rapid growth, resistance to treatment and tendency to infiltrate surrounding brain tissues, making surgical measures difficult as well. Instinctively, our family’s initial understanding came from the internet sources. Unfortunately, a simple web search reveals that this type of cancer is labelled as incurable. It was stated that the median length of survival of glioblastoma patients after a diagnosis is 15-18 months. Another study in Neuro-Oncology Advances concluded the survival rates for one year, two years and five years were 38.6%, 7.6%, and 1%, respectively. All sources we turned to revealed the same fate. The statistics and facts didn’t shout; they almost echoed. There was no sign of hope, just a losing battle. But what if we’re only sharing one side of the story? What if, in the midst of statistics and survival facts, we are missing the human will to fight? We often say that hope is the guiding factor of life. Perhaps it is also the key to fighting cancer. The disease itself may be detrimental, but the story doesn’t have to come to an end without putting up a good fight. A study conducted by Stanford University School of Medicine caters to demonstrate that while treatments like chemotherapy can have toxic effects on different parts of your body, like the heart, negative mindsets may be equally toxic for the patient's long-term journey. Mindsets and styles of thinking assist in making sense of complex states and motivate healthy behaviours. The deep-rooted values and beliefs of a patient about suffering and the healing process of cancer directly influence their psychological and behavioural state. Studies by placebo and neuroimmune activation cater to show that eventually, these factors influence the outcome of the patient’s journey. Marcus Aurelius suggests that while we cannot control external events, we can control our response to them. It is crucial to allow the patient to fight their own battle. The cognitive shift of having hope reduces psychological suffering and helps in enhancing engagement and emotional regulation during treatment. It was Frankl, in his theory of logotherapy, who argued that meaning-making is the primary motivational force in humans even when put in unfavourable circumstances. In such cases, a patient with cancer is encouraged to find a deep-rooted goal to work towards, like sharing their story or simply deciding to fight another day. The ambition to achieve the goal itself becomes a psychological anchor, navigating through the struggles of the body. Now focusing on a scientific perspective, emerging research caters to showing that the way of thinking of a patient can be directly linked with health outcomes of the nervous and immune systems. Initially, when my grandmother was encouraged to start doing meditation, it would often confuse me. When I researched more about it, I came to realise that the emergence of a tumour, its rapid progression, and the process of cancer growth are often affected by stress. This is normally regulated by norepinephrine, epinephrine and cortisol – also known as the “big three” hormones. Our body’s response to any sickness can be categorised in terms of cellular and molecular components. One relevant factor is the protective immune response that assists in eliminating infections and cancers, enables tumour immune-based treatments and mediates the body’s early response against cancer. In cancer, it’s important for the immune system to remove cancers that naturally trigger a response or tumours that have been made easier for the body to recognise and attack. Numerous studies report that chronic stress suppresses protective immunity. The “big three” hormones and steroid hormones are stressors that interfere with the pathway of protective immunity. Thus, it is said that chronic stress suppresses the functioning of the body’s immune response by decreasing immune cell redistribution between different parts of the body. Furthermore, studies have catered to demonstrate that different types of advanced-stage cancers can be influenced by ongoing stress over a long period of time. For example, when my mother spoke to cancer specialists, they would often emphasise how patients who experience higher levels of daily stress and symptoms of depression – induced by oneself or their environment – tend to have a weaker immune system. Specifically, their body is unable to fight infections and diseases, which makes recovering from cancer very difficult. Another postulate to focus on is that a weaker immune system also makes it harder for one to tolerate chemotherapy. This treatment is already extremely difficult on one’s body. Having a weak immune system makes the body more vulnerable to the side effects of chemotherapy. Patients with poor immune responses are likely to face excruciating side effects like fatigue and infections and require longer recovery time between treatment cycles. This can lead to delays or changes in the treatment plan, which may affect the overall effectiveness of the therapy. On the other hand, having a more positive mindset encourages the body to have stronger immune responses that help the body recover more quickly, manage the side effects better and not experience any delays in the required treatments. Hence, peace of mind and physical health are both essential factors when facing a disease like cancer. One case study highlights the direct impact of chronic stress on patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. The study suggests that patients who experience less anxiety after surgery tend to show stronger immune activity. This is because their body produces helpful micromolecules like IL-2 that support the growth and survival of important immune cells in the body. A higher level of IL-2 indicates that the immune cells are activated efficiently and the body is able to build stronger protection. Therefore, this caters to show that mental well-being is vital in physical recovery. With the enhancements in cancer care, one thing is prominently clear: healing is not solely done by the medium of surgery or biological process. It also requires a will to fight and emotional transformation. While treatments like chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation remain the most proactive solutions for treating cancer, the mind-body connection proves to be a powerful driving force. So, while cancer begins in our body, the journey of the patient is dictated by the mind. Looking back at my grandmother’s battle, it is clear that when we stop looking at cancer as a “losing battle” and choose to view it as a “challenge that must be encountered with resilience”, we restore hope. Today, my grandmother remains with us, completely cured from the disease that doctors themselves called incurable. That is all the proof I need to know that our mind is way stronger than we perceive and that hope is the medicine that our body prescribes.Sana Arora is a student at Plaksha University pursuing a degree in Bachelor of Technology. With a keen interest in biology and a passion for innovation, she aims to blend scientific research with entrepreneurial strategy to drive impact. Sana is determined to work at the intersection of healthcare, business, and consultation. IS IT CANCER OR THE THOUGHT OF CANCER THAT DESTROYS US? | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

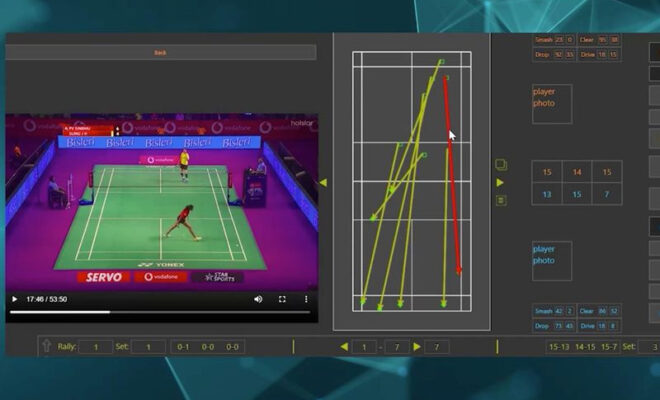

Game Theory Acquires Matchday.ai To Enhance Player Matches (2025-06-23T11:12:00+05:30)

By The Techy Guy Game Theory is an Indian startup that makes sports more fun and interactive like video games, and has taken a big step. They have joined hands with another company called Matchday.ai. This is a big deal because it’s the first time Game Theory has bought another company since they got some funding, where Nithin Kamath played a major role. Nithin Kamath is well known for his work with Rainmatter and is quite a big name in the startup scene. Sudeep Kulkarni, the person who started Game Theory, is bringing Matchday.ai into the fold. The aim here is to make playing sports a lot more exciting and give a feel similar to playing a sports video game. So, think of it like bringing the cool tech of video games into real-life sports. By acquiring Matchday.ai, Game Theory is looking to make their system smarter. This means they can make better matches for players and help casual players improve just like professional athletes do using advanced tech. So, in a way, they’re bringing the expertise used by top sports stars to everyday players. Now, the brain behind this Matchday.ai technology is quite something—it can see and understand movements in sports very closely, which is what Game Theory wants to use to make its offerings even better. Game Theory is not about sitting and playing video games; it’s about bringing that video game experience to real-life sports. They’re working on making physical sports accessible in a way that feels as engaging and competitive as playing a sports game on a console or computer. So, instead of just playing football on a screen, you might be able to get a similar engaging experience while actually playing football on the field. To make the acquisition of Matchday.ai smooth and successful, Game Theory had a guide by their side—Prequate Advisory, the company that ensured this partnership went without a hitch. They’re like the experts who handle the business side of these big moves. Game Theory is all set to make playing sports a whole new experience with some really clever technology! Game Theory Acquires Matchday.ai To Enhance Player Matches |

Michelle de Kretser wins the Stella Prize with a genre-bending questioning of art and expectation (2025-06-05T13:33:00+05:30)

Lucy Neave, Australian National UniversityMichelle de Kretser, one of Australia’s most innovative and internationally recognised writers, has been awarded this year’s Stella Prize for her seventh novel, Theory & Practice – currently longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award. This is De Kretser’s first Stella Prize win. She is one of only a few women to have won the Miles Franklin twice, for The Life to Come (2018) and Questions of Travel (2013), both shortlisted for the Stella. Theory & Practice explicitly engages with Virginia Woolf’s ambitions for her final book. Woolf had initially wanted The Years to function as an essay spiked with fiction. The Stella Prize judges said: “in her refusal to write a novel that reads like a novel, de Kretser instead gifts her reader a sharp examination of the complex pleasures and costs of living”. Theory & Practice might look like a slender volume at 183 pages, but it is substantial in its themes, engaging with the slippages and gaps between the theoretical and the practical. These include the gulf between feminist ideals and reality, and between mothers and daughters – both literal and metaphorical. Defying genre and formThe Stella Prize, established in 2012 to address the underrepresentation of women writers, expanded from 2019 to include the work of non-binary writers. It has increasingly rewarded writers from diverse communities – culminating in this year’s shortlist, entirely composed of women of colour – and experimental work.

Last year’s prize went to Waanyi writer Alexis Wright for her genre-defying novel, Praiseworthy. Critics have described Theory & Practice as “form-melding” and, as Eda Gunyadin put it in The Conversation, using “a hybrid form to comment on form itself”. The book itself describes wanting to explore the “messy gap” between theory and practice in a form that suits its subject. Scary Monsters, de Kretser’s previous novel, winner of the UK Rathbones Folio Fiction Prize, also experimented with form and style. It was composed of two novellas with distinct voices and settings. Readers had to flip the book upside down to read the second narrative, reflecting the “upside down” experience of refugees. Hypocrisy, privilege and messy idolsTheory & Practice repeatedly challenges expectations, calls out established wisdom, and prioritises everyday lived reality over theory. The novel opens with a fluid, compelling narrative about a man travelling in Switzerland. But on page 12, this ends with the words: “At this point, the novel I was writing stalled”. By abruptly ending the all-encompassing dream it has created for the reader, Theory & Practice challenges how fiction usually works. As the novel continues, the narrator says: “I was discovering that I no longer wanted to write novels that read like novels.” Instead, she wants “a form that allowed formlessness and mess”. After this genre-bending start, Theory & Practice follows a first-person narrator in 1980s St Kilda, in inner Melbourne, who is studying a Masters in English and conducting a consuming love affair with a mining engineering student named Kit. This world is evoked in economic, compelling prose. Theory & Practice repeatedly examines how the “theoretical” has been bent to serve the interests of the privileged. In an essay-like early section, the narrator describes the co-opting of theory to perpetrate violence by an Israeli military commander. Later, she explains how theory was deployed to identify “an authentically female way of writing”, which she finds limiting. De Kretser’s characters co-opt theory to justify their relationships, too: Kit describes his open relationship with his girlfriend Olivia as “deconstructed”. Theory & Practice reveals the hypocrisy of those who fail to apply the ideas they supposedly believe in to their own lives. The narrator, who believes herself a feminist, abandons the ideal of sisterhood in her relationship with Kit, despite realising Olivia is “suffering”. The narrator’s maternal literary figure, her “Woolfmother”, fails her on a practical level: Woolf’s diaries reveal her to be “a snob and a racist and anti-Semite”. This tussle with the complexities of a literary hero is a key aspect of the novel. Ahead of the cultureDe Kretser’s novel demonstrates how practical ways of being are more vital and life-changing than any theory. Lenny, a gay friend, backs up his beliefs with action, volunteering on a helpline for gay men during the AIDS crisis. He points out theory’s limitations:

In The Value of the Novel, English literature professor Peter Boxall argues “the genetics of the novel form” allow it to “exceed” its conventions. The novel, he believes, remains “ahead of the culture in which it is written and received”. Theory & Practice’s expectation-busting form readily enables it to escape the conventions of fiction and nonfiction. Largely set in the 1980s, the novel’s shifts in time, including to the present day, help it speak to contemporary concerns: including the uses and misuses of theory, and the importance of political action. In the process, it speaks a multitude of complex truths. Lucy Neave, Associate Professor, English, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Nobody knows how consciousness works – but top researchers are fighting over which theories are really science (2025-06-04T12:44:00+05:30)

Science is hard. The science of consciousness is particularly hard, beset with philosophical difficulties and a scarcity of experimental data. So in June, when the results of a head-to-head experimental contest between two rival theories were announced at the 26th annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness in New York City, they were met with some fanfare. The results were inconclusive, with some favouring “integrated information theory” and others lending weight to the “global workspace theory”. The outcome was covered in both Science and Nature, as well as larger outlets including the New York Times and The Economist. And that might have been that, with researchers continuing to investigate these and other theories of how our brains generate experience. But on September 16, apparently driven by media coverage of the June results, a group of 124 consciousness scientists and philosophers – many of them leading figures in the field – published an open letter attacking integrated information theory as “pseudoscience”. The letter has generated an uproar. The science of consciousness has its factions and quarrels but this development is unprecedented, and threatens to do lasting damage. What is integrated information theory?Italian neuroscientist Giulio Tononi first proposed integrated information theory in 2004, and it is now on “version 4.0”. It is not easily summarised. At its core is the idea that consciousness is identical to the amount of “integrated information” a system contains. Roughly, this means the information the system as a whole has over and above the information had by its parts. Many theories start by looking for correlations between events in our minds and events in our brains. Instead, integrated information theory begins with “phenomenological axioms”, supposedly self-evident claims about the nature of consciousness. Notoriously, the theory implies consciousness is extremely widespread in nature, and that even very simple systems, such as an inactive grid of computer circuitry, have some degree of consciousness. Three criticismsThis open letter makes three main claims against integrated information theory. First, it argues this is not a “leading theory of consciousness” and has received more media attention than it deserves. Second, it expresses concerns about its implications:

The third claim has provoked the most outcry: integrated information theory is “pseudoscience”. Is integrated information theory a leading theory?Whether you agree with integrated information theory or not – and I myself have criticised it – there is little doubt it is a “leading theory of consciousness”. A survey of consciousness scientists conducted in 2018 and 2019 found almost 50% of respondents said the theory was either probably or definitely “promising”. It was one of four theories featured in a keynote debate at the 2022 meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, and was one of four theories featured in a review of the state of consciousness science that Anil Seth and I published last year. By one account, integrated information theory is the third-most discussed theory of consciousness in the scientific literature, out-stripped only by global workspace theory and recurrent processing theory. Like it or not, integrated information theory has significant support in the scientific community. Is it more problematic than other theories?What about the potential implications of integrated information theory – its impact on clinical practice, the regulation of AI, and attitudes to stem cell research, animal and organoid testing, and abortion? Consider the question of fetal consciousness. According to the letter, integrated information theory says “human fetuses at very early stages of development” are likely conscious. The details matter here. I was the co-author of the paper cited in support of this claim, which in fact argues that no major theory of consciousness – integrated information theory included – posits the emergence of consciousness before 26 weeks gestation. And while we should be mindful of the legal and ethical implications of integrated information theory, we should also be mindful of the implications of all theories of consciousness. Are the implications of integrated information theory more problematic than those of other leading theories? That’s far from obvious, and there are certainly versions of other theories whose implications would be every bit as radical as those of integrated information theory. Is it pseudoscience?And so, finally, to the charge of pseudoscience. The letter provides no definition of “pseudoscience”, but suggests the theory is pseudoscientific because “the theory as a whole” is not empirically testable. It also claims integrated information theory wasn’t “meaningfully tested” by the head-to-head contest earlier this year. It’s true the theory’s core tenets are very difficult to test, but so too are the core tenets of any theory of consciousness. To put a theory to the test one needs to assume a host of bridging principles, and the status of those principles will often be disputed. But none of this justifies treating integrated information theory – or indeed any other theory of consciousness – as pseudoscience. All it takes for a theory to be genuinely scientific is that it generates testable predictions. And whatever its faults, the theory has certainly done that. The charge of pseudoscience is not only inaccurate, it is also pernicious. In effect, it’s an attempt to “deplatform” or silence integrated information theory – to deny it deserves serious attention. That’s not only unfair to integrated information theory and the scientific community at large, it also manifests a fundamental lack of faith in science. If the theory is indeed bankrupt, then the ordinary mechanisms of science will demonstrate as much. Tim Bayne, Professor of Philosophy, Monash University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What’s a trade war? (2025-05-30T12:06:00+05:30)

|

This article is part of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance. Thanks to US President-elect Donald Trump, the term “trade war” is back in the headlines. Trump campaigned successfully on a platform of aggressive trade policies, and since being elected, has only doubled down on this posture. On Tuesday, he threatened Mexico and Canada with new 25% tariffs on all goods, and a separate “additional” 10% tariff on China “above any additional tariffs”. While the term might conjure up dramatic images of battlefield tactics, the real economic impact of any looming trade war is likely to hit much closer to home – both for Americans and the rest of the world. Global supply chains are deeply interlinked. That means a major trade war initiated by the US could push up the prices of all kinds of goods – from new cars to Australian-inspired avocado on toast. To understand where we might be headed, it’s worth unpacking the metaphor. What exactly is a trade war? What are the “weapons” countries use? Perhaps most importantly – can either side win? The weapons of warThere are many “weapons” available to a country in a trade war, but tariffs are often a popular choice. This is simply an extra tax put on a product as it crosses a border as an import. For example, all else equal, Trump’s proposed 25% tariff on goods from Canada would bump the price of a $32,000 Canadian-built car up to $40,000. Tariffs are usually paid by whoever is importing the product and paid to the government of the importing country. That means the extra cost is almost always passed on to consumers. Why would any government want to force prices up like that? Because it gives locally produced goods without the tariff a cost advantage. That might seem like a reasonable way to protect local industries, but tariffs can backfire in unexpected ways. Consider how many foreign parts go into “American-made” products. When a car rolls off a US assembly line, it’s built from thousands of components – many of which have to be imported from other countries. If those parts face tariffs, manufacturing costs rise for domestic producers, and prices rise further for domestic consumers. Limiting what comes inThere are other trade restrictions, too, referred to as non-tariff measures. Quotas are one example. These place limits on how many units of something can be imported during a specific time period. Returning to our earlier example, the US could choose to set an import quota on that same Canadian-made car of one million per year. Once that limit had been reached, no more Canadian cars could enter the country, even if consumers wanted to buy them. This artificial scarcity can drive up prices because demand stays the same while supply is restricted. Like tariffs, the theory is that those higher prices for imports will cause consumers to favour locally manufactured goods. More covert weaponsSome other trade restrictions are more covert – arguably easier to conceal and deny. Imagine your export permit was cancelled without explanation or your shipment of lychees was left rotting in a foreign port for reasons that seem to be political. Or your country suddenly disappears from another country’s electronic export system, meaning that you now cannot export anything there at all (this happened to Lithuania, which was removed from China’s customs database). These are the sorts of trade war tactics that my research team and I have been studying in our Weaponised Trade Project. We have collected nearly 100 examples of coercive trade weapons over the past decade, used by a wide range of countries against their competitors. Today’s tariff is tomorrow’s trade warOnce deployed, trade weapons can cause political tensions to escalate rapidly. Other countries often retaliate with their own tit-for-tat measures. From there, they can escalate into full-blown trade wars. The new president of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, has already warned this may happen, in response to Trump’s threats earlier this week.

We’ve had some nasty trade wars before. One of the most notorious examples from history were the “beggar-thy-neighbour” tariffs and other protectionist policies of the interwar years, which deepened the Great Depression. You might remember this from the classic movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: When countries restrict trade, prices typically rise for consumers, jobs can be lost in industries dependent on foreign materials, and trade and economic growth slow on both sides. Politicians might claim victory when their foreign competitors make concessions, but economists generally agree that trade wars create more losers than winners. Lisa Toohey, Professor of Law, UNSW Sydney This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What is comparative advantage? (2025-05-29T11:47:00+05:30)

|

Martin Richardson, Australian National University

This article is part of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask leading experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance. For the best part of two centuries, the principle of “comparative advantage” has been a foundation stone of economists’ understanding of international trade, both of why it occurs in the first place and how it can be mutually beneficial to participants. The principle largely aims to explain which countries produce and trade what, and why.

And yet, even 207 years on from political economist David Ricardo’s first exposition of the idea, it is still frequently misunderstood and mischaracterised. One common oversimplification is that comparative advantage is just about countries making what they’re best at. This is a bit like saying Macbeth is a play about murder – yes, but there’s quite a bit more to it. Costs represent missed opportunitiesComparative advantage does suggest that a country should produce and export the goods it can produce at a lower cost than its trading partners can. But the most important detail of the principle is that cost is not measured simply in terms of resources used. Rather, it is in terms of other goods and services given up: the opportunity cost of production. An asset like land used for agriculture has an enormous range of other potential productive purposes – such as growing timber, housing or recreation. A production decision’s opportunity cost is the value forgone by not choosing the next best option. Ricardo’s deep insight was to see that focusing on relative costs explains why all countries can gain from comparative advantage based trade, even a hypothetical country that might be more efficient, in resource-use terms, in the production of everything.

Imagine a country rich in capital and advanced technology that can produce anything using very few resources. It has an absolute advantage in all goods. How can it possibly gain from trading with some far less efficient country? The answer is that it can still specialise in those goods at which it is “most best” at producing. That’s where its advantage relative to other countries is greatest. Who’s best at producing wheat?Here’s an example. In 2023, Canada’s wheat industry produced about three tonnes of wheat per hectare. But across the Atlantic, the United Kingdom yielded much more per hectare – 8.1 tonnes. So which country has a comparative advantage in wheat production? The answer is actually that we can’t say, because these numbers are about absolute efficiency in terms of land used. They tell us nothing about what has been given up to use that land for wheat production. The plains of Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba are great for growing wheat but have few other uses, so the opportunity cost of producing wheat there is likely to be pretty low, compared with scarce land in crowded Britain.

It’s therefore very likely that Canada has the comparative advantage in wheat production, which is indeed borne out by its export data. Why does it matter?We have recently seen a lot in the news about industrial policy: governments actively intervening in markets to direct what is produced and traded. Current examples include the Future Made in Australia proposals and the US Inflation Reduction Act. Why is comparative advantage relevant to these discussions? Well, to the extent that a policy moves a country away from the pattern of production and trade governed by its existing comparative advantage, it will involve efficiency losses – at least in the short term. Resources are allocated away from the goods the country produces “best” (in the terms discussed above), and towards less efficient industries. It’s important to note, however, that comparative advantage is not some god-given, immutable state of affairs.

Certainly, some sources of it – such as having a lot of natural gas or mineral ore – are given. But innovation and technical advances can affect costs. A country’s comparative advantage can therefore change or be created over time – either through “natural” changes or through policy actions. The big hard-to-answer question concerns how good governments are at doing that: will claimed future gains be big enough to offset the losses? Does everybody gain from international trade?Supporters of free trade are often accused of arguing that everybody gains from trade. This was true in Ricardo’s early model, but pretty much only there. It has been understood for centuries that within a country there will typically be gainers and losers from international trade. When economists talk of the mutual gains from comparative-advantage-based trade, they’re referring to aggregate gains – a country’s gainers gain more than its losers lose. In principle, the winners could compensate the losers, leaving everybody better off. But this compensation can be politically difficult and seldom occurs. But the concept can’t explain everythingThe theory of comparative advantage is a powerful tool for economic analysis. It can easily be extended to comparisons of many goods in many countries, and it helps explain why there can be more than one country that specialises in the same good. But it isn’t economists’ only basis for understanding international trade. A great deal of international trade in recent decades, particularly among developed nations, has been “intra-industry” trade. For example, Germany and France both import cars from and export cars to each other, which cannot be explained by comparative advantage. Economists have developed many other models to understand this phenomenon, and comparative-advantage-based trade is now only one of a suite of tools we use to explain and understand why trade happens the way it does. Martin Richardson, Professor of Economics, Australian National University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |